By STEPHEN WICKENS

Apparently, Toronto is suddenly rolling in cash.

By STEPHEN WICKENS

Apparently, Toronto is suddenly rolling in cash.

I and at least two others within a bun’s toss were pleased to see the Accra Beach Hotel honoured at the closing banquet of a recent Caribbean Tourism Organization conference in Guyana.

The official wording of the press release said “the Sustainable Accommodation Award went to the Accra Beach Hotel and Spa in Barbados for positively impacting the local supply chain and community whilst minimizing negative environmental impact, and contributing to conservation of local culture.”

I’m trying to learn more about what this all means and I have emails out to CTO staff. But as a travel journalist who also writes about urbanism, it’s great to see the CTO’s 13th annual Sustainable Tourism Conference recognize that walkable, vibrant communities are just as important to vacation spots as they are in our home cities.

On a basic level, my wife and I had a great stay at Accra Beach a few months back. The price was reasonable, our room and the beach were excellent, staff were friendly and, as a bonus for active people who like to swim lengths, the pool was among the best I’ve found in the Caribbean.

But Accra and the Rockley Beach area proved to be special because the resort is so well integrated within a thriving stretch of shops, services and restaurants patronized by both locals and tourists. This is a case where tourists are really strengthening the local economy and where the local businesses are really contributing to the tourism experience.

The virtuous cycle has benefits beyond the bottom lines of business. All day and into the evening there are eyes on the street and feet on the sidewalks, as urbanist Jane Jacobs would have pointed out. This is probably not a place where a mugger would want to ply his trade and the pedestrian instinctively senses that.

This mingling of locals and tourists adds much to a vacation experience on a human level. And when vacationers feel safe out walking beyond their hotels, they don’t need to rent cars or take cabs anywhere near as often.

Contrast that with the experience of an all-inclusive compound or a resort on a lovely but isolated stretch of beach.

When we talk of sustainable travel, we often hear about initiatives to protect rainforests or minimize waste from cruise ships. We talk of finding ways to offset the carbon emissions of jets or make solar and wind power viable for resorts and their small island countries. These are all good and important subjects. But on the south coast of Barbados, something as simple as a comfortable environment for pedestrian interaction illustrates sustainability and environmentalism at its organic best.

Cheers, to the Accra Beach, but please share this honour with your many neighbours.

This item was first posted at City Builder Book Club, where you’ll find lots of great posts about chapters from Jane Jacobs’s 1961 classic, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Visit and read, and get out and walk. Go on a Jane’s Walk http://citybuilderbookclub.org/2012/03/stephen-wickens-on-the-need-for-small-blocks/

By STEPHEN WICKENS

Apart from a brief post at Torontoist, the erasure of Roy’s Square for the 1 Bloor condos went unmourned. And two stops down the Yonge subway, the Aura condos rise, snuffing hopes of those who cared that a block of Hayter Street was shut in 1978.

The Death and Life of Great American Cities has been around 50 years and Jane Jacobs has been gone more than five, but ‘The need for short blocks’, the second of her four conditions indispensable for generating diversity, remains overlooked.

On Condition 4, density, converts abound, though understanding is often dangerously simplistic. It’s tough to gauge how we fare on No. 3, but mingling buildings of different ages is widely discussed. As for No. 1, land-use mixes, there has been progress, though it will remain limited till people really get the crucial differences between primary and secondary uses.

Short blocks, alas, tend to be viewed as insignificant if noticed at all. It’s no surprise that one-offs such as Roy’s Square are forgotten. But multiplied over a city or a metropolitan area, and the absence or loss of short blocks undercuts street life and economic viability. Implications are lasting and hard to correct.

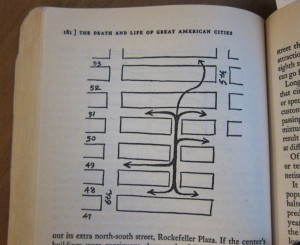

In Chapter 9, “The Need For Small Blocks,” Jacobs combines common sense, basic observation and rudimentary maps of streets in Manhattan’s West 80s, between Central Park and Columbus Avenue, to illustrate how longer blocks isolate pedestrians, limiting their options and leaving many streets “stagnant backwaters.”

“The supply of feasible spots for commerce rises considerably” when street grids increase chances for pedestrians to turn corners. Even slight variations in sidewalk traffic will make or break nascent enterprises, so it’s easy to see how seemingly minor changes to street patterns trigger virtuous and vicious cycles.

The chapter, the book’s shortest at just nine pages, explains a mystery that baffled New Yorkers after street-deadening elevated rail lines were removed from 3rd Avenue and 6th Avenue. On the West Side, where the blocks were long, the move had little effect. On the East, with its short blocks, revitalization erupted.

Of course, cities are complex and organic, so it’s foolish to consider conditions in isolation, something Jacobs reminded me of in a 2005 discussion on block-length effects in Toronto.

Referring to the underperforming Sheppard subway, she decried local media’s fixation with the new residential density along the line. “A few tall buildings don’t constitute healthy urban form. Even near the stations, people aren’t walking in large numbers,” she said, pointing out that land uses remain separated and there aren’t enough primary uses attracting people.

Furthermore, because the area can’t provide a real mix of building ages for generations, she said it’s doubly essential the other diversity generators be present. “As long as the blocks are long, you can be sure the area will be off-putting for pedestrians and, for the most part, economically barren,” she said. “Density in the absence of short blocks is usually trouble.”

Regarding Danforth Avenue east of Pape, Jacobs indicated that those who noticed the area’s decline as car ownership grew and after subway replaced the streetcar in 1966, tend to overestimate transportation’s role. “If this is like typical blue-collar neighbourhoods from the early 20th century, you’ll find there was significant loss of industry after the war,” she said. “These losses devastated the area’s primary-use mix.”

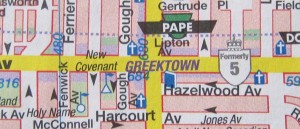

Then, after a warning about how misleading maps can be, she said my quest to understand the Danforth’s split personality should “start with a good, scaled map; compare block lengths.”

Sure enough, the things she identified in New York apply here. To the west of Pape Ave., in Greektown, where businesses and sidewalks thrive, it takes less than a minute to walk most blocks at an easy pace. Sometimes 45 seconds will do.

The first south-side block east of Pape is unbroken all the way to Jones Avenue and takes nearly four minutes to walk. The long-block east-west streets to the south have little real connection the Danforth. And all through the areas further east, often called the “Other Danforth,” where a “blight of dullness” arises, long blocks dominate at least one side of the street until the rail corridor veers close enough to do further damage by truncating neighbourhoods to the south.

From Roy’s Square, to the Danforth, to New York, Europe and beyond, the role of vitality’s four generators is universal. But while we often add density and mixes of uses, and we sometimes let our buildings age, we rarely add streets and shorten blocks.

It troubled Jacobs to the end.

The best way to thank her for explaining this crucial detail, which was hidden in plain view all along, is to ensure we leave as many small blocks as possible to our descendants.

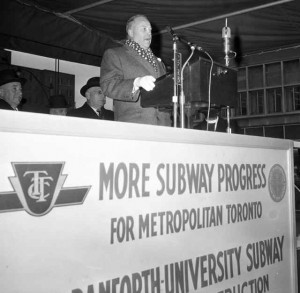

Once upon a time, a much smaller and poorer place called Toronto went ahead and built subways without any funding assistance from Ottawa or Queen’s Park

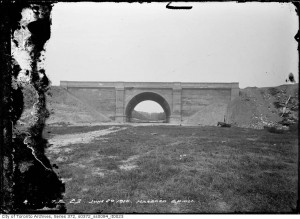

This story first appeared in the Toronto Star on Feb. 3, 2012. All photos were taken by Toronto Telegram photographer Peter Ward and are published here courtesy of the York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections.

By STEPHEN WICKENS

Torontonians have seen countless transit plans in recent years, but even the wildest fantasy versions haven’t considered time travel — and maybe that’s a shame.

If we could all hop a Red Rocket to Nov. 16, 1959, and get off at University Avenue and Edward Street, we could witness an event locals might consider unbelievable. And if planners and politicians were among the time travellers, local transit talk might be more relevant and productive, even before the ride back to 2012.

***

The guy in the ill-fitting red hard hat operating the steam shovel for the sod-turning ceremony is Leslie Frost, premier since 1949. Mayor Nathan Phillips is among the dignitaries, along with “Big Daddy” Fred Gardiner, the Metro chairman who would prefer that expressways get priority. Allan Lamport, a former mayor who successfully argued that subways would be a better long-term investment, will take a turn with the earth-moving equipment after Frost is done.

Observant guests from the 21st century might note the absence of any giant cheque for the photo-op. And there is no spin-doctor’s slogan on a lectern placard, no printed backdrop screens lauding Queen’s Park for creating jobs or tackling gridlock. Of course, Frost has good reason to not blow his horn: he doesn’t bring a penny to the project. Instead, he delivers only a speech, a stern warning to municipal politicians that they’re on their own, that they’d better not get mired in debt for this $200-million University-Bloor-Danforth subway plan — 25 stations over 16 kilometres.

***

By now, you know the job got done, and it was accomplished on budget in just six years and three months.

“It was a remarkable feat,” says veteran civil engineer and consultant Ed Levy, who has written a forthcoming book on Toronto’s transportation history. “It took guts to go ahead without provincial funding, especially when you consider this was a much smaller and poorer city, and tunnelling technology was relatively primitive.

“The truth seems unbelievable today, after decades of paralysis and sickening blunders on the rare occasions when Queen’s Park has provided funding.”

In 1959, it had been five years since the original Yonge line from Union to Eglinton had opened (funded largely by fare-box surpluses) and Toronto was eager to get building again, even if the province wouldn’t help.

To figure out how we did it, Levy says several factors must be considered. We were willing to put a surcharge on property taxes, though the towns of Mimico and Long Branch objected. But the biggest factor is almost certainly that “the economics are pretty well guaranteed to work when you put subways in the right places ” — already dense, transit-supportive parts of the city.

“We don’t have a lot of that and, obviously, we can’t build only downtown, but it was madness to stop building subways in old Toronto in the 1960s,” says Levy, whose first engineering job involved plans for shoring up buildings for the University line tunnels.

“Look at cities that have been able to keep expanding; they’ve all built steadily from the middle out. London’s tubes go a long way out, but all go through the core. [And though few tourists may realize it, 55 per cent of London Underground is actually above ground, and when Toronto was good at building subways on time and on budget, we went open trench through low-density areas north of Bloor on the Yonge line, or above ground once the subway rolled into Scarborough at Victoria Park.]

“We might yet be able to make the economics work in the suburbs, but it will take big changes to our whole approach, lots of up-zoning and big increases in the densities of those areas.”

Fifty-five per cent of the tab for the University and Bloor-Danforth lines came from property taxes levied by Metropolitan Toronto, a senior local government abolished in the 1998 amalgamation. The Toronto Transit Commission, which didn’t need taxpayer subsidies for operations until the early 1970s, was profitable enough under its zone-fare system and a primarily urban operations area to pay 45 per cent. Eventually, under Frost’s successor, John Robarts, Queen’s Park guaranteed a $60 million loan, allowing a work speed-up that saw the line from Woodbine to Keele open in 1966 rather than 1969.

Can hiking property taxes make a difference?

The Toronto Board of Trade estimates we’d get only $22 million a year if we raised residential rates 1 per cent, but considering most people in 905 pay at least 25 per cent more in property taxes, it may be an option.

Transit advocate and blogger Steve Munro says one thing working against us now is that all construction costs have risen faster than the rate of inflation. It’s tough to quantify this, but he appears to be correct. The Bank of Canada says $200 million in 1959 is worth roughly $1.6 billion today, and there’s no way we could build those lines and the Greenwood maintenance and storage facility for the latter figure.

“We also used cheaper cut-and-cover box tunnels, rather than the current deep bore approach,” Munro says. “The stations were rudimentary, often with only one exit. It also didn’t hurt that, 40 years earlier, people thought long-term and built that lower deck on the Bloor viaduct, not that anyone would have considered tunnelling under the Don River in the 1960s.”

But Munro, like everyone else interviewed for this article, comes back to the relationship between land use and transit and the need to reconnect mutually supportive forces if we’re ever to make costly infrastructure pay and keep expansion ongoing.

“Some will argue that, ‘You don’t see lots of towers along the original Bloor-Danforth,’” Munro says. “But it worked because transit demand was already well-established for kilometres north and south of the new subway. The street could probably use redevelopment now, but it serves as a great example that effective urban form doesn’t have to include high-rises.”

Transport and energy consultant, author and former city councillor Richard Gilbert made a similar point in a 2006 paper titled “Building Subways Without Subsidies.” In it, he calculated a combined 30,000 to 40,000 jobs and residential units within a square kilometre of each station on the $2.6 billion Spadina-York subway extension would allow it to pay for itself in 35 years.

“You could do all that without going over seven storeys,” he says, adding there has been little development on the Spadina line in 35 years of operation. This extension into York shows few signs of paying back any better. People have to understand that subsidies are a substitute for density, and that’s fine if money is no object,” he says. “We’re making the same mistake again on Eglinton. We’re blasting more than $8 billion at it and the province hasn’t set any performance-based conditions. There’s not a single requirement about density around and above the stations.

“If we don’t fix this, if we don’t put some real effort into figuring out how the public can get back even some of this money, we have no hope of obtaining real value for the $50 billion Metrolinx is supposed to spend on the Big Move.”

Eric Miller, director of the Cities Centre at the University of Toronto, says “we’ve been fooling ourselves for decades” with the idea that development and urbanization will automatically follow subways in places first developed around the car.

“It was always a well-crafted myth that the TTC and others generated,” Miller says. “Building heavy rail is a necessary but not sufficient condition to generate high density in the suburbs. We have to get really serious about ensuring that density, walkability and rich mixes of land uses happen and we can’t waste time.”

In January, TTC vice-chair Peter Milczyn made an encouraging but generally unreported announcement at the city planning and growth management committee meeting. He said he and TTC chair Karen Stintz would work to ensure all future stations had at least some development upstairs from the start. But some see this and initiatives such as Metrolinx’s Mobility Hub concept as mere timid steps in the right direction; that small islands of urbanity in ever-growing seas of car dependence won’t do and that the full costs of sprawl must be identified and recaptured.

John Sewell, former Toronto mayor and author of The Shape of the Suburbs, argues the entire GTA had better come to grips with the urgency because Metrolinx’s investments in the 905 area are even less likely to pay for themselves than the subsidy-driven services we pushed into the older 416 suburbs beginning in the late 1960s.

“The GTA has to compete globally, and we’re guaranteeing ourselves negative real returns on a grand scale,” Sewell says, adding the financial burden will almost certainly further erode long-term political will to properly fund transit, even in places where transit is cost-effective.

“Because of the way we’ve built the outer suburbs, any type of transit we put out there will require massive subsidies for operations,” Sewell says. “That’s the problem with suburban form; sprawl is unsustainable — literally, financially unsustainable. Mississauga is just learning this now.”

Planner Ken Greenberg thinks our slide into bad habits began even before the Bloor-Danforth opened. “One great mistake of that era is that we started detaching land use from infrastructure investment. On Yonge, at St. Clair, Davisville and Eglinton, you have, in effect, little cities. Lots of people live and work near those subway stops. For the most part, such is not the case on the Bloor-Danforth and Spadina. Something was suddenly and fundamentally off kilter and it took Toronto out of the realm of what other cities have been doing consistently.”

Levy and Gilbert also point to other trends that were developing by the late 1960s. “People will be irritated by my saying this, but our transit problems began when the suburbs began dominating at Metro,” Levy says. “Some of it may be coincidence, but the loss of the zone fares and the way Scarborough, Etobicoke and North York developed means subways may never pay for themselves there, and Vaughan is another story altogether. They don’t have the density, but they have the votes.” [The Toronto-East York community council area, 6,348 people per square kilometre, is more than twice as dense as Scarborough and Etobicoke, and 63 per cent denser than North York.]

University of Toronto historian Richard White makes the case that suburbanites did contribute because a building boom in Scarborough, Etobicoke and North York made the Metro tax surcharge particularly lucrative, but he agrees the suburban form in those former boroughs and the end of the zone-fare system made public transit expensive.

Gilbert, former research director at the Centre for Sustainable Transportation, says even the much-pined-for funding formula started in the 1970s by former premier Bill Davis — a 75 per cent subsidy for new infrastructure and 50 per cent toward operating deficits — probably worsened our problems long-term. “Those subsidies obscured the true cost of providing urban transit in suburban places, so it’s no surprise that they keep getting larger. This is a classic case of a perverse subsidy.”

That brings us to planner Pamela Blais, who has spent at least 15 years studying how hidden “perverse” subsidies encourage sprawl much more effectively than planning guidelines and growth boundaries fight it. But the author of Perverse Cities makes clear she would prefer bigger transit subsidies from senior governments because the public service role justifies them.

She says that if we want to get on with building transit infrastructure and delivering good service across the GTA, we must address the fact that the lower the density and the more we segregate land uses, the more expensive it is to deliver all network services, and that includes gas, hydro, mail, sewers, water, and telecommunications.

“When everybody pays the same average price, rather than the marginal cost of service provision, people in the densest areas overpay to subsidize people further out, where they largely don’t pay their fair share. Trying to outlaw sprawl won’t work, but if we properly identify the hidden cross-subsidies and get the pricing signals right, people will make the right decisions,” she says, citing development charges and the market-value assessment approach to property taxes as areas in need of reform.

Paul Bedford was Toronto’s chief planner when the city produced its first official plan after amalgamation, and linking transit and land use was central to that mission. He hopes we can find “consistent leadership over time, so plans don’t keep changing with each municipal election.

“The other key is that the Metrolinx development strategy has to be really bold, not just with planning new infrastructure, but with funding sources for operations and maintenance,” says Bedford, who is still waiting to learn if he will be reappointed to the Metrolinx board. “We need the funding plan this year,” he says, adding he thinks plans for a downtown subway should be moved up the priority list. “We’re at least 30 years behind, and we’re going to be adding the equivalent of Greater Montreal in the next 25 years. Heaven help us if we allow much of it to be car-dependent sprawl.”

But Greenberg points out that sprawl is marching on. “Yes, we’re having trouble getting transit infrastructure built, but our problem is more land use than transportation,” he says. “We’re getting some intensification in a few places, but go to King City or Uxbridge, places like that on the fringes, it’s still ongoing, full, industrial-strength, traditional sprawl. More and more people living in environments where they have no practical choice but to drive everywhere. We have policies intended to fight it, but way too many incentives to continue as is. We’re sucking and blowing at the same time and the illusion is that we’re wealthy enough to afford it.”

Sewell, meanwhile, is skeptical that we can remake the suburbs. “It’s really hard to retrofit any place built for the car, they haven’t been evolving into urban places. If it’s going to work, it’s going to take a lot more than density. We need that real mix of land uses and short blocks. Planners have to keep the pedestrian in mind at all times and we need the financial incentives.

“If it’s going to happen, it’s going to take a really long time and I don’t know that we have it. Maybe if we took that train back to 1959 we could warn them, but I don’t know if that would help, either.”

By STEPHEN WICKENS

Toronto’s desperate for brilliance on the transit file.

And if we get more than a flash of it for Sheppard Avenue in coming years, we may be indebted to an immigration officer who visited Seoul in 1965. Such are the wonderful chains of events available when looking back over longer lives – not that we’re calling Raymond Cho old.

Without that bureaucrat, Cho wouldn’t have been talked into coming to Canada. And, without Cho, the next phase of this interminable and painful Sheppard debate would almost certainly be more of the same. But after more than 20 years on council, Cho’s suddenly a rookie TTC commissioner. His background is in social work. He has a master’s, a PhD and a sense of humour.

He also has a big problem.

Cho represents Ward 42, Toronto’s northeast corner, and it’s the likely plight of his constituents that best highlights a gaping hole in the discussion.

Even with a new light-rail line — the recommendation of an “expert” panel that reviewed a narrow menu of options for council — transit will be messy for voters in Cho’s ward.

Consider a Ward 42 resident attending York University or Humber College, or working on Finch West or at Vaughan Metropolitan Centre. The trek might start with a walk to a stop and a wait for the Neilson, Morningside or Progress bus to get to the new line.

LRT would provide service to Don Mills station and another transfer point, this time for a five-stop subway ride to Yonge. From there, it could be two more stations on a northbound train to pick up the Finch West bus for a ride over to another LRT starting at Keele. Or it might make sense at Sheppard-Yonge station to grab a bus to Downsview, before transferring to a northbound Spadina train to York or Vaughan or the Finch LRT.

Round-trip, that’s up to 12 transfers, and studies have found transit riders’ wait-time perceptions are often out by a factor of three.

Apparently, since the March 5 council meeting, we’re back heeding transit experts, and experts say minimizing transfers is a key to public transit’s competitiveness with private cars.

Respected transit people — including David Gunn, Richard Soberman and Ed Levy — made this point at a 2008 symposium put on by the Residential and Civil Construction Alliance of Ontario. None of those who spoke is anti-LRT or pro-subway, but all felt Transit City, which council seems eager to re-embrace, had big flaws, starting with Sheppard-Finch corridor disconnects. They indicated that if we put LRT lines on Sheppard east and Finch west, we better find a way to make them one, even if it means converting the Sheppard subway to light-rail.

TTC planners may have listened because, for a brief period, Transit City was augmented to link the lines via Don Mills Road and Finch East, though that solution isolates the Sheppard stub, wasting a billion sunk-cost dollars.

Cho didn’t ask for this mess, but then it wasn’t his idea to move to Canada. His brother was the would-be immigrant, but brought Raymond along as an interpreter. That’s when the Canadian official persuaded Cho to apply, setting in motion the events that have landed him on the Sheppard hot seat.

Cho offers a thoughtful “hmmm,” when it’s pointed out that, simultaneously, we talk of seamless Metrolinx-led transit across the GTA while preparing to lock into a series of time-wasting hurdles for east-west travel within the city. “The question is a very valid one,” Cho says when asked what he’ll tell constituents. “This is one area I’ll take a very close look at.”

Of course, at council, Cho must endure lobbying from pro-subway and pro-LRT zealots. It will test his claim to have risen above the left-right rift that has deprived Toronto of sanity since amalgamation. But Cho must know something about resolve, growing up in Japanese-occupied Korea, losing his dad in a cholera epidemic and, as a teen, keeping out of the line of fire in the Korean War. And though Canada wasn’t welcoming when he arrived, he became a great immigration success story.

“I remember asking, why did I come to this stupid country?” he says, recalling racial intolerance and long shifts as a dishwasher, waiter, miner and janitor. “At one point, I even picked worms. It was hard, but it was a great education, much more valuable than my doctoral degree. I learned to listen. I learned how to talk to anyone.”

He says by the early 1970s, once he’d brought his fiancé from South Korea and settled in Toronto, he fell in love with Canada.

“I knew this was my country.”

Now, at 75, does he have the energy for such a baptismal firefight in the unfamiliar transit portfolio?

“C’mon, compared to Hazel McCallion, I’m a teenager,” he says.

Councillor Cho has since announced he will support the panel’s LRT recommendation. No word yet on what he’s telling his constituents.

The story first appeared in the Globe and Mail on Jan 8, 2005. The Dover Square tower never got built, though the city has seen an incredible high-rise boom ever since.

By STEPHEN WICKENS

Luis Berroa vows not to take sides, but says he can’t avoid neighbourhood talk about plans for a new apartment tower south of Bloor Street West on Dovercourt Road.

“Everyone talks high-rise now; this fight will be ferocious,” the drywaller/roofer says while eating breakfast at the counter in Billy’s Souvlaki Place on Dovercourt.

“The people are against the building. Me? I’m torn. I like all construction. It’s good for the economy.” But Mr. Berroa says he knows why his neighbours are angry. “Nobody wants tall buildings close to their house.

“If I owned [my home], I’d be mad, too.”

The battle he speaks of stems from Sterling Karamar Property Management’s plan to add a 285-unit building to the three Dover Square towers that went up in the 1960s.

The Dufferin Grove Residents Association, formed in response to the Dover Square plan, says the 13-storey building would eat up nearly half the immediate community’s green space, overburden amenities and lower property values.

Members of the residents association plastered notices aimed at bolstering opposition with a dramatic rallying cry: “Save our neighbourhood! Don’t wait until it’s too late. . . . Do we want another St. James Town?”

Elsewhere in the city, similar fights are becoming increasingly common. The Minto Place tower now being built at Yonge Street and Eglinton Avenue prompted probably the city’s nastiest high-rise squabble in recent years. North Toronto resident Raymond Tong remains so upset over the Ontario Municipal Board’s decision to allow the building that he has been lending support to the Dufferin Grove residents. Those fighting Dover Square are also supported by Mike Kilpatrick, who is battling proposals to add high-rise towers in the Warden corridor of southwest Scarborough. And residents at the south end of Church Street are battling to stop a development at 40 The Esplanade.

According to the website UrbanToronto.ca, about 100 residential buildings of 30 storeys or more are currently proposed, approved or under construction in the GTA. As Toronto prepares to grow by an estimated three million residents over the next three decades, is there any way to avoid acrimony?

Former mayor John Sewell says yes, but suggests that much of the conflict stems from the official plan itself, even though it hasn’t been officially implemented yet. The new plan, which will replace seven plans from pre-amalgamation Toronto, encourages more intensive, transit-supportive land use.

“It seems to say intensification is good, no matter what form it takes,” he says. “People generally agree intensification is a smart thing, but they object to buildings that are entirely inappropriate for where they are planned.”

He says much of the acrimony would be unnecessary if people understood that we can have high density in a low-rise format.

“The densest development in the city is the St. Lawrence community [100 units an acre]. Nothing in it is higher than 10 storeys. It really works. People like living there. But just up the road, a developer — and the city — want to give us an awful high-rise,” he says of Cityzen Urban Lifestyle’s plan for 40 Esplanade. He also blasts Ted Tyndorf for supporting it.

Mr. Tyndorf, the city’s new chief planner, blasts back, calling Mr. Sewell’s statements “simply not true.”

“What you’re seeing is not the product of a document and a policy paper. It’s the product of a market demand and the maturity of a large urban centre. High-rise is not the only form [needed to meet the city’s intensification goals],” Mr. Tyndorf adds, before mentioning some of the same low- and mid-rise successes that Mr. Sewell cites.

But he defends Cityzen’s plan, saying “it’s really on the edge of downtown, and across the street from an existing 35-storey building. It’s not an inappropriate context.”

Mr. Tyndorf says early public consultation — ideally, before a developer has even made an application — is the key to wise and peaceful resolutions. An example he raises involved a year of meetings that led to plans for a proposed high-rise project at the old Eglinton subway bus terminal. “It has the approval of the same ratepayers and the same city councillor [Michael Walker] who fought the Minto application so hard.”

Although it’s been more than two years since Minto got OMB approval to exceed the densities and heights set out in the old official plan, anger lingers. Mr. Tong, who opposed the project, thinks the OMB is much too understanding of the developer’s position. “Why do we elect city councils or go to the trouble and expense of producing official plans if the OMB is going to ignore them?”

Anne Johnston, a 30-year city councillor who lost her seat in 2003 largely because of her support for the Minto deal, shares concerns that the OMB has too much power, but also suggests city residents who want to avoid high-density living altogether are being unrealistic. “A lot of people, call them NIMBYs if you will, fear or hate all growth. They don’t understand that a city is not healthy unless there’s steady growth.”

Karl Jaffary, a lawyer who represents developers and residents groups (including those who fought Minto and some Yorkville high-rises), has noticed the recent rise in neighbourhood battles, and he doesn’t sound optimistic that peace will break out any time soon.

“The existing official plan seems to have little meaning for the city planning staff, and the new plan would do nothing to restrain them in any event,” says Mr. Jaffary, who served alongside Mr. Sewell as a city councillor in the early 1970s. “We seem to be back very much to a let’s-make-a-deal sort of planning,” he says of a system that allows developers to exceed official plans in exchange for funding other ventures, such as seniors’ housing or parks. “The city seems to be flying by the seat of its pants.”

Dovercourt and Bloor is a hive of activity on New Year’s eve afternoon, and only 11 people have to be questioned to find 10 with an opinion on Dover Square — seven against, two in favour, and the “torn” Mr. Berroa.

Mario Calderon calls Dover Square opponents “nuts.”

“Sure the rents are high,” the west-tower tenant says, “but the buildings are well maintained. Maybe if more apartments are built, landlords will have to lower the rent.” Mr. Calderon also says that “except when the ice-cream truck comes, or when the landlord has the free barbecue,” the green space is not that well used.

A few days later, Andrew Munger is unhappy to hear Mr. Calderon’s views. “On a warm June or July evening, there will be 100 to 150 people there,” he says. “And there’s a constant stream of pedestrians all year on the path through the site.”

Mr. Munger, president of the Dufferin Grove Residents’ Association, likes Mr. Tyndorf’s idea about getting residents involved early in the planning. But he says, “That’s exactly what did not happen here. We were more or less shut out of the process.

“We’re not against intensification and not totally against high-rise, but you have to be careful not to overwhelm a community,” he says. “The existing complex is high-rise, but it’s integrated with the community. All plans we’ve seen [from the developer] would encroach significantly on the green space.”

Marvin Sadowski of Sterling Karamar replies that “some green space will go, but it will be minimal,” and “many of those who talk about the loss of green space are people who also complain regularly about the noise of kids playing there.” He adds that the original plan called for a taller building that would have taken up less space, but the city and neighbours said it was too high. And although the number of units did go from 187 to 285, they’re smaller units.

The citywide fighting is all “a NIMBY thing,” he says. “I think a lot of it is precipitated by people who have been, perhaps, coached as to what to say at public meetings.”

And so the war continues.

Mr. Jaffary will be representing Sterling Karamar.

Mr. Munger says his group now has to settle on a strategy. “Is there an acceptable compromise to be had? Do we gamble on the OMB?”

The next official round in the fight is Feb. 1 at an OMB pre-hearing session.

THE DENSITY ISSUE

City planning chief Ted Tyndorf and former mayor John Sewell disagree about some controversial high-rises, but both cite the success in east downtown of the St. Lawrence community, the city’s densest development.

At 100 units an acre, it doesn’t have any buildings taller than 10 storeys. And St. Lawrence may not be an aberration.

Census data and statistics provided by the city indicate that Dover Square, central to one ongoing high-rise battle, is in Ward 18, which has Toronto’s densest population: 10,347 people per square kilometre. But only 16.2 per cent of Ward 18’s households are in buildings of five or more storeys, compared to a city average of 37.6 per cent.

And while high-rises are common in some dense areas of Toronto, Ward 17, which has the city’s lowest percentage of households in buildings of five or more storeys (5.8 per cent), is the third-densest of the 44 wards at 8,180 people per square km.

Mr. Tyndorf says the numbers indicate that the city has to look at all options to make intensification work, but also that Ward 18 may not face such a shortage of green space with more high-rises.

Marvin Sadowski, executive vice-president of developer Sterling Karamar, says it comes down to profit. “We provide good housing at what we think is a fair price, but we don’t provide social housing. Based on economics, if it’s going to be rental, it has to be high-rise.”

Nearly everything about the way the TTC is structured and governed must change if good advice, wise planning and quality transit at a reasonable price are to be priorities. Otherwise, Andy Byford will go the way of his predecessors.

Good luck Andy Byford!

Next to crime and trauma scene cleanup specialist, leading the Toronto Transit Commission is the worst job in your new home city.

The fact that your three most recent predecessors were forced out by politicians barely scratches the surface of what’s wrong with this gig. If you are the man for the job and if you dig deep, you’re sure to conclude that starting points must be a new relationship with elected officials, a new corporate culture and a total restructuring, including a spun-off entity that fosters commercial integration of transit and land-use.

Customer service panels, town halls and the addition of citizen commissioners can only diddle with the symptoms of a decades-long decline.

Yes, it was petty and counterproductive for those five commissioners to axe Gary Webster, but you’re surely smart enough to see through the political posturing, even if many seemingly intelligent Torontonians swallowed whole. You must have seen similar backstabbing and disingenuousness while working in Australia and the U.K.

TTC managers have been pressured to tailor advice for political purposes going back at least to the 1970s, when we somehow chose to maroon stations of the Spadina subway in the median of an expressway.

Good but powerless experts foresaw woes of the Scarborough RT well before it was built. And those who felt in 1989 that we should cut our losses and scrap that line were effectively silenced.

Pressure to manufacture a case for the Sheppard subway and play down the urgency of a long-proposed line through the downtown core, beginning 30 years ago, will cast a shadow over many debates you’ll have to lead.

In fact, there’s a good case to be made that all pending plans for Eglinton, Sheppard, Finch or a northerly extension of the Yonge subway are trouble if the so-called Downtown Relief Line can’t jump the queue. (Little-known fact: tiny, cramped Yonge-Bloor station sees more daily passenger movements than Pearson airport and Union Station combined).

Of course, politics also played a big role in the rush to create the Transit City plan in March 2007, and to sell it to the public ever since. There are people still shaking their heads over a decision by one TTC manager to attend and appear prominently at the launch of Adam Giambrone’s brief run for the mayoralty.

The latest census shows Toronto has 2.615 million transportation experts. But, while many realize transit is a problem of organized complexity, most seem to prefer simplistic debate — black or white, left or right, subway or light rail. This suits our ideologically riven council members who want us to shut off our brains and pick sides. It’s also essential to mainstream media, which increasingly cater only to those with short attention spans.

But it doesn’t help anybody make wise decisions.

Compounding the mess, Andy, is that Toronto wasn’t big when the car became king. The pre-amalgamated cities of Etobicoke, North York and Scarborough have about half the density of old inner Toronto, and the gap isn’t closing. Those outer areas were designed for cars and drivers, but are now populated by people who need transit. Alas, the built form makes quality cost-efficient service delivery tough.

Our long-standing assumption that pushing subways into suburbs would automatically drive urbanization turned out to be bunk. However, attempts to get the TTC to seriously consider how to adapt and adopt creative funding models and aggressive value-capture tools, like those used in the Far East, have been met with disinterest at best (while still a city councillor in 2003, David Miller got the TTC to agree to report on transit development corporation models like the one in Hong Kong, but despite repeated requests over years, the TTC has been unable to produce evidence that it did any work on the project).

Even the mayor’s office, which purports to favour private-sector involvement, had the most interesting parts of Gordon Chong’s report on subway financing chopped before publication (make sure your copy is an early uncorrected proof containing Chapter 7, “Other Value Capture: Revenue Generation Options”).

If we truly believe transit spending is an investment, returns on the investment have to start becoming a priority. If we do that, it forces intelligent debate on the real relative costs of subways and light rail. We’re likely to still conclude LRT is the way to go in many cases, but the debate will have been honest.

Sorry if you probably know all this, but talk with your vice-chair, Peter Milczyn; he seems increasingly attuned to the possibilities and the shortcomings of our previous model.

Make sure you thank your predecessor for eventually standing up and opposing the loony idea of burying light rail under Eglinton East, but you might ask him where was he on the possibly-as-wasteful design and funding models for the ongoing Spadina-York subway extension. Deep-bore tunnels through low- and no-density areas and grandiose standalone stations make this project far more costly than it needed to be up front, while hindering the long-term development processes that can help it pay back.

Yes, some bad things happened under Webster, but overall he was just the latest fall guy for a dysfunctional organization.

For years, one of Toronto’s most revered and entertaining transit experts has been saying, off the record and only partly in gest: “The fastest way to find yourself unemployed in this town is to speak the truth.”

Some part of that wisdom will always be true.

You’ll have to choose your battles, even in your interim role. But unless you get extremely wise help to start radically altering the rules of the game, you’re guaranteed to lose – as is Toronto, again.

Toronto greatest lost river may be buried, but it’s never been dead

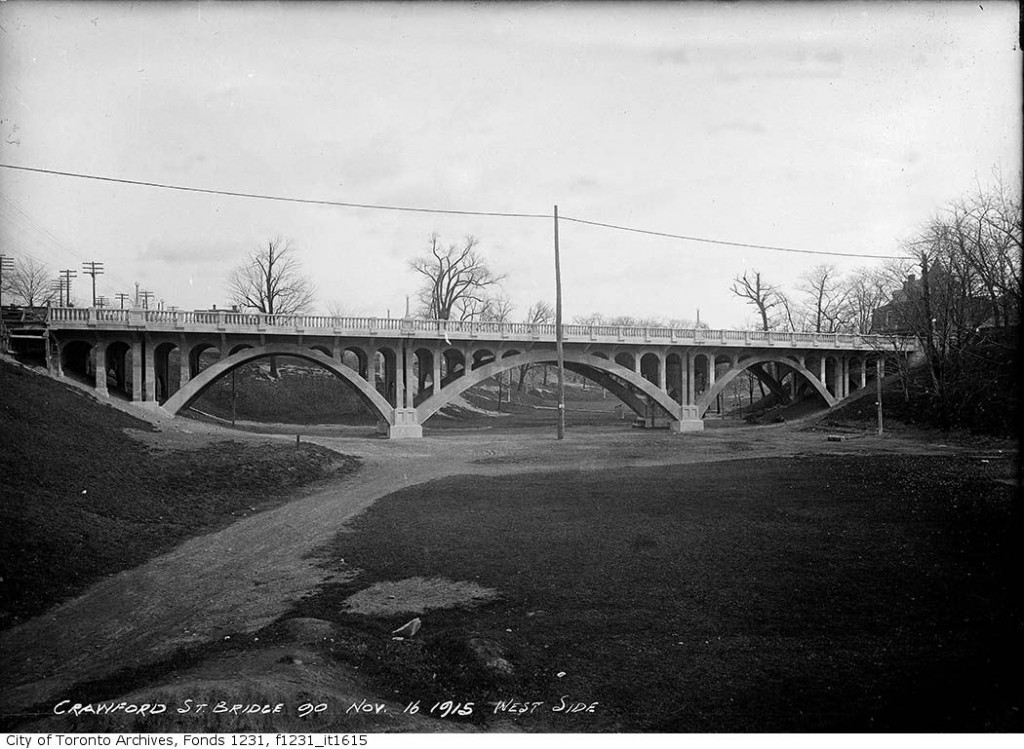

This story first appeared in The Globe and Mail on October 29, 2005. The Garrison linkage group and its meetings died shortly thereafter. But Prof. Bernd Baldus hopes to revive things as part of a retirement project. There have been no reports of guerrilla archeology at the Harbord and Crawford bridges.

By STEPHEN WICKENS

Barring a flood of near-biblical proportions, no one will ever again paddle from Fort York to Christie Pits. And the fishing won’t be good any century soon at the Grace Street dip, where London Stream might still empty into Garrison Creek, south of Bloor Street and 10 or so metres underground.

But in certain circles, there’s serious talk of “guerrilla archeology” — digs under cover of darkness to expose parts of the Harbord Street and Crawford Street bridges, the last of at least 20 that once spanned Toronto’s largest buried river.

“It’s to be expected, and it might be a good thing,” James Brown says about the prospect of insurgents armed with shovels roaming Bickford and Trinity Bellwoods parks at night. “People are frustrated.”

At issue is the lack of progress on a project — approved by city council in 1998 — to reconnect the parks and potential parkland of the largely invisible Garrison valley from north of St. Clair Avenue to the lake. It would include bike paths, walking trails and storm-water retention ponds that would be integral to Toronto’s drainage and irrigation.

“This isn’t about nostalgia or mere parkland,” says Mr. Brown of Brown + Storey Architects, who produced the plan with his wife and partner Kim Storey in 1994 — at their own expense — based on decades of research and years of input from scores of community volunteers. “This project is about creating something of real long-term use to the city. Water is an incredibly valuable resource and we have trees dying of thirst, but we still see rain as waste to be disposed of.”

Garrison Creek flows under parks, streets, houses, schools and supermarkets, just as the water does in more than a dozen other buried Toronto streams. It’s largely encased in tunnels we built from the 1860s on, to hide ravines that we had turned into open sewers and dumps for ash and trash.

Some have mused about recreating the early-1800s state of nature that allowed canoes to travel up the creek to Bloor Street. The Garrison project took a more realistic approach, but that might not be enough to save it.

A decade ago, it wasn’t unusual for 400 people to show up at Garrison Creek community meetings. Now, those who have been in for the long haul are drifting away, fearful the project is irretrievably lost in the city’s bureaucracy.

“You can only attend so many public meetings before the lack of tangible progress wears you down,” says committee member Bernd Baldus. “There are some really good and dedicated people at City Hall . . . but, overall, bureaucrats are sucking the life out of this.”

Mr. Brown and Prof. Baldus, a University of Toronto sociologist, say the city missed the point by emphasizing the words “Garrison Creek” through street signs and brass letters set in pavement, rather than the potential of real experience and historical connection.

Prof. Baldus suggests that the city wasted an opportunity last year, when Crawford Street was repaved. “They could have exposed part of the bridge, used some of the original cedar block-style paving, put up railings,” he says. “Until last year, there were clues that a bridge is there. Now, you can’t tell at all. No wonder people talk about guerrilla digs . . . and at Harbord, you need only dig about two feet to really start exposing the span.”

Prof. Baldus got hooked on the Garrison project after picking up a piece of litter on the street. It turned out to be a flyer that said a stream ran under his neighbourhood. He has now been involved for 11 years, but he says he won’t stick around for a 12th unless citizens can reclaim some control from the city, and unless an annual meeting with Councillors Joe Pantalone and Joe Mihevc can be held before each budget period.

“My office is always open to Mr. Baldus; he deserves an award for tenacity,” Mr. Pantalone said. “But on the Crawford Bridge, there was community consultation. There was no majority view that said, ‘Spend $6-million the city doesn’t have to restore the bridge.’ We did ensure the resurfacing was done in a way that, 50 or 100 years from now, should people have the money to unearth it, the bridge will be there. It’s an archeological element — you don’t destroy such things.”

As for public meetings, Mr. Mihevc says it’s likely they will be held.

“The key for this group’s success is to develop bite-sized projects that council, in tight budget years, can sink their teeth into.”

But for all the talk of frustration, there are signs of hope. We may have poisoned and buried our creeks alive, but we never killed Garrison, literally or figuratively.

Earlier this month, more than 200 people showed up dressed in blue for the Human River, a Garrison-tracing hike put on by the Toronto Public Space Committee, the North Toronto Green Community and the Toronto Field Naturalists. The latter two have held “lost river walks” around the city for a decade, teaching people to read the bends and subtle dips in our streets, listen for roars from sewer grates or look for indicator trees such as willows.

Garrison Creek has recently provided artistic inspiration. Stephen Marche’s short story of that title was nominated for an O. Henry Prize in 2002; Erín Moure’s translation of the epic poem Sheep’s Vigil by a Fervent Person, which features references to the buried river, made the 2002 Griffin Poetry Prize shortlist; and Bluemouth Inc. mounted the critically acclaimed play Something About a River in 2003.

Globe and Mail columnist John Bentley Mays wrote in 1994 that “Garrison Creek can lay fair claim to being Toronto’s most famous waterway never seen,” except by an elderly man he had just interviewed.

But in the spring of 2004, running water appeared under a bridge on Bathurst Street, east of Fort York, where Garrison emptied into Lake Ontario from 10,000 years ago until the late 19th century. Fort York administrator David O’Hara, who was with the parks department when the discovery was made, still can’t confirm the water is Garrison Creek. “But we know it’s not coming from a broken water main,” he says, “and it’s not from the sewers — storm or sanitary.”

He says Toronto Community Housing, which plans to build nearby, has a hydrologist on the case. “It sure looks like it’s Garrison, and that’s exciting for us at the fort,” Mr. O’Hara says. “This creek is essential to our history.”

Erin Wood, a Toronto Public Space Committee volunteer who helped organize the Human River walk earlier this month, is among those who only recently became aware of the city’s underground streams and the plight of the Garrison. “It’s amazing to think there are a dozen of these streams in central Toronto alone,” she says. “We’re told Toronto is flat with a grid of streets, but now I see bends and dips — and I know why they’re there.”

And has she heard anything about guerrilla archeology?

“Let’s just say I was involved in some guerrilla gardening this spring. A dig at the Harbord Bridge might be really neat. Who knows?”

If you’re not bringing subways to your urban areas, you have to bring urbanity to your suburban station catchment areas. Anything else is obscenely wasteful

This column ran in the National Post on February 14, 2011. It’s business as usual with a wasteful approach to stations on the Spadina-York subway extension, but TTC vice-chairman Peter Milczyn made an encouraging announcement at the January 5, 2012 planning and growth management committee meeting. He said he will push to ensure we never again build such standalone stations.

By STEPHEN WICKENS

Apparently, Steeles West subway station will get a hip, downtown façade. Too bad it won’t get a real, downtown built form, hip or otherwise.

Politicians keep telling us capital and operating funds for transit are scarce, so why do we even consider standalone subway stations, let alone permit the plans and discussions about them to descend into architectural wankfests?

While we blow $857-million on stations for the $2.6-billion Spadina-York extension, many seemingly intelligent Torontonians debate the relative costs of LRTs and subways and puzzle about how some places on this planet make real rapid transit affordable and effective — even profitable on occasion.

Subways can pay for themselves in truly urban settings. We proved that a half-century ago along Yonge and Bloor streets and University and Danforth avenues. Present-day Hong Kong has turned subway building into a profitable business for all concerned.

The key is to understand and act upon the transit-land use relationship and capture the values created by rapid transit. In the 1950s and ’60s, for example, a much smaller and poorer Toronto could build subways without help from Queen’s Park and Ottawa because the existing urban form made passive value capture possible. Tax-base and ridership increases were enough.

But to make subways viable in greenfield environments and suburban areas originally designed for the car, aggressive and directed value capture strategies are needed. If you’re not bringing subways to your urban areas, you have to bring urbanity to your suburban station catchment areas. Japanese railways such as Hankyu and Tokyu pioneered these transit-oriented development models nearly 100 years ago.

In old inner-city Toronto, we had so much early urban success that we tolerated some wasteful standalone stations — though they were small and utilitarian. We should have adjusted the station and vicinity planning demands for our first forays into suburban Scarborough, North York and Etobicoke, but senior governments willingly subsidized the waste. Short-term it appeared to work, but it is one factor that contributed to the erosion of our political will to properly fund transit.

In Hong Kong, MTR Corp. builds and operates the subway system and has been profitable every year since 1979, largely because it’s also a major property developer with latitude. Malcolm Gibson, MTR’s chief of project engineering, told me seven years ago the key is that “tunnels and tracks will always be costly, but stations can be gold mines.”

To make that work, especially in a suburban environment such as the Spadina-York extension, the subway builder (that’s us, the taxpayers of Ontario) must ensure every station is located in the centre of an intense mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly node.

Because the space above the station carries the biggest premium, we must ensure the basic station — platforms, escalators et cetera — are part of the basement/foundation of a major development from the start. If you wait till the line is built and then try to sell air rights or build above a working station, huge amounts of the marginal subway-generated real estate premium is gone forever. Note that the most successful stations in Toronto have almost no footprint at the surface. They’re not monuments to “starchitect” ego.

In a North American context, the chances are beyond remote we’ll ever get subways for free, but it’s realistic to demand that developers pay for our stations. If we can’t do it, we’re putting the stations in the wrong place and/or the land-use nexus potential hasn’t been properly factored into the funding model.

Meanwhile, back in Toronto, as the march of folly continues, we get “hip facades” and irrelevant comments about the Steeles West plan from respected architects, university professors and their students.

Discuss landscaping, oxidized surfaces, the size of the lettering on the station, the latest celebrity gossip and the Maple Leafs if you must, but the one question that matters about Steeles West station is: How many thousands of people will perform daily functions such as living, working, shopping and playing within an easy and pleasant five-minute walk of the turnstiles?

Mentions of the station’s green roof and LED lighting, meanwhile, should make thoughtful environmentalists retch.