Strategically piggybacking onto Metrolinx’s upgrades will help us better nurture urbanization at Scarborough Centre while freeing up capacity on the overloaded inner-city subway system. Extending the Bloor-Danforth, no matter how many stations we include, aggravates the crowding in its best-case scenario.

By STEPHEN WICKENS, ED LEVY and STEVE FRY

—————————————————————————————————-

NOTE: Even though the SmartSpur/SER option would make Mayor Tory’s SmartTrack idea far more useful to east Toronto than in its originally conceived form, it proved to be such a threat to the one-stop Scarborough subway’s viability that all study of SmartSpur was killed on March 31, 2016, at city council after some backroom arm-twisting.

—————————————————————————————————-

One city councillor declared peace in our time and if we weren’t well into the 21st century a hat-tossing ticker-tape parade might have seemed appropriate.

Maybe a tad premature, but what a month January 2016 has been on the transit file: The mayor accepted evidence that SmartTrack’s western spur doesn’t make sense, while city planning said it will study a transitway on King Street. In Scarborough, planners and politicians claim to have found $1-billion to reinvest in Eglinton-Crosstown LRT extensions – west toward the airport and east from Kennedy to the U of T campus. (Environmental assessments are already done for those extensions, meaning plans could be shovel-ready in time to qualify for the new federal government’s promised infrastructure program.)

Can it get any better?

Excuse our sunny ways, but yes it can if John Tory is willing to re-examine how SmartTrack best piggybacks onto Metrolinx’s Regional ExpressRail in Scarborough. According to well-placed sources who’ve contributed to a new report, RER upgrades in the works will permit at the very least 14 trains an hour in each direction between Union Station and Markham. RER needs only four trains; what can we do with the other 10 or even 12?

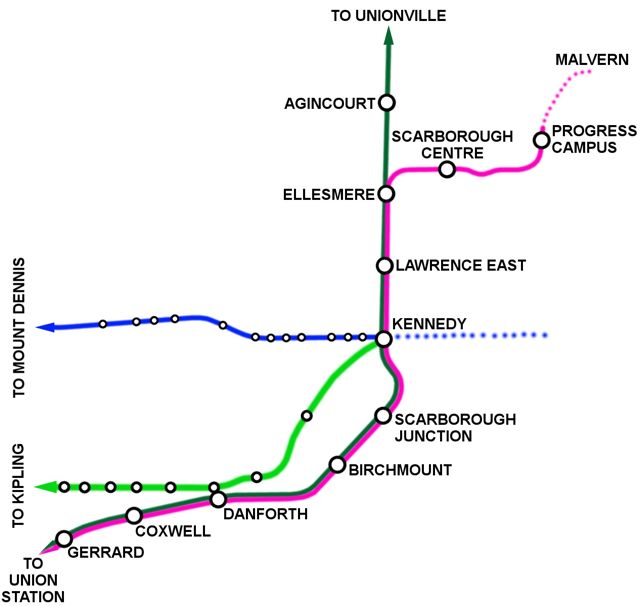

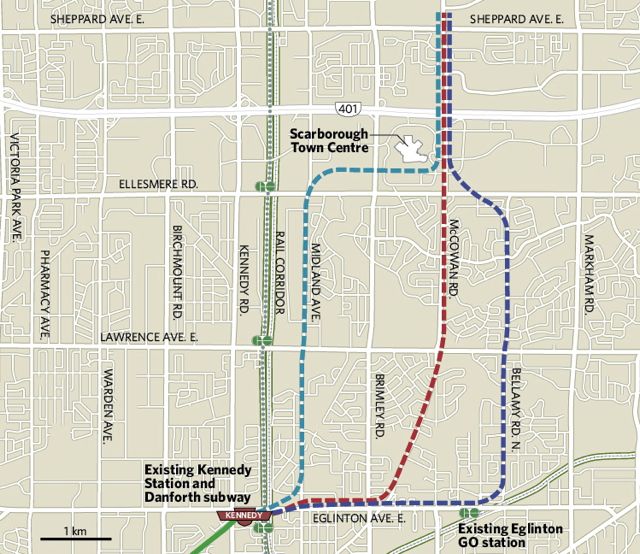

Before SmartTrack was a gleam in the mayor’s eye, transportation researcher Karl Junkin was examining GO electrification possibilities for think tank Transport Action Ontario (the Star’s Tess Kalinowski wrote about his work in 2013). Further study now confirms one piece of TAO’s report, branching a line off Metrolinx’s tracks east to Scarborough Town Centre (almost following the current, near-defunct SRT corridor), is not just doable but can be done for $1.1-billion. That’s $1.4-billion less than the estimate for the one-stop subway idea that made news last week – $2.4-billion less than the previous three-stop plan.

Junkin’s idea, known to some as SmartSpur but now rebranded as Scarborough Express Rail (SER), can make the east part of SmartTrack smarter than the mayor ever dreamed. Aside from saving money, benefits are huge for many stakeholders if we link Kennedy to STC using GO’s corridor instead of tunnelling under Eglinton Avenue and McCowan Road.

– Scarborough residents would have a one-seat ride downtown from STC without transfers at Kennedy or Bloor-Yonge. Time savings to Union could be as much as 20 minutes. SER would include Lawrence and Ellesmere stations (and could add ones at Birchmount and Coxwell-Monarch Park).

– Residents of East York and the old city who have trouble boarding jammed Bloor-Danforth trains in the morning rush hour at stops west of Main Street would get more capacity. Thousands fewer would squeeze through overcrowed Bloor-Yonge station onto the otherwise unrelieved lower Yonge line. Compare that with making the Bloor-Danforth longer, which would only aggravate crowding for all concerned (if it doesn’t drive more people out into other modes of transportation).

– Short term, for those working to urbanize Scarborough Centre, SER’s one-seat ride to the core provides only a small advantage over a direct tunneled link via the Bloor-Danforth. But SER has much greater long-term potential as it can easily be extended north and east to Malvern on the route previously reserved for LRT ($1.4-billion can certainly get us to Centennial College’s Progress Campus).

Toronto’s playing catch up, but urgency may finally be focusing minds in high places. We now have a mayor big enough to admit when he’s wrong, while city staff have taken over transit planning from the TTC and appear open to creativity (criticize the one-stop subway idea all your want, but if nothing else it has broken a political logjam). Maybe Metrolinx will get aboard and save us another $500-million by keeping the Crosstown LRT on the surface, rather than tunneling into and out of Kennedy station.

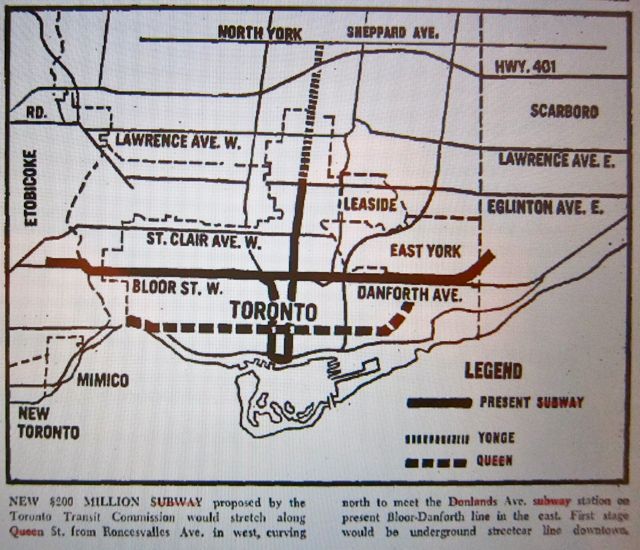

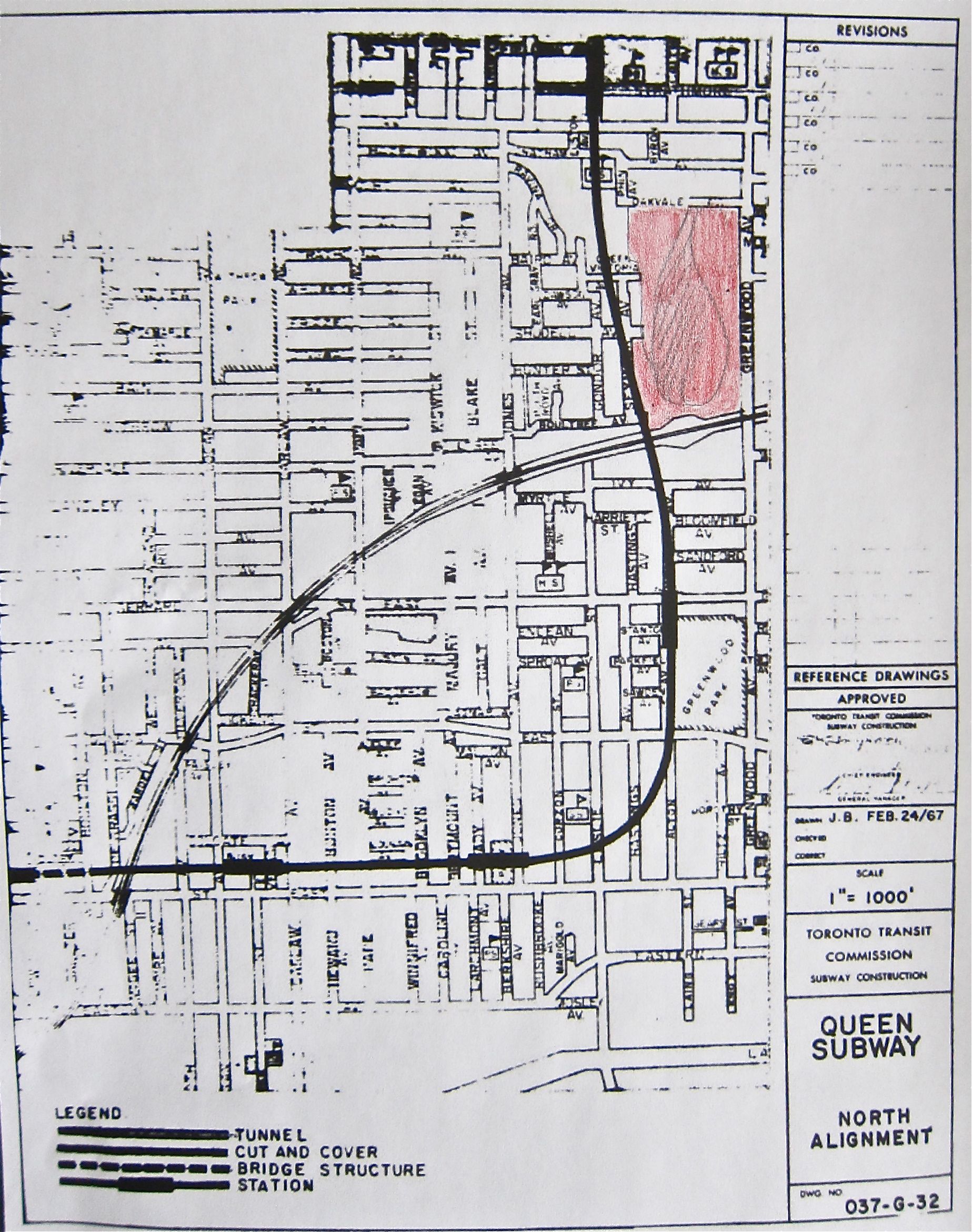

Yes, capacity at Union will be seriously constrained by RER and SER, further increasing the urgency of another subway through the core and up into Don Mills (the long-dreamed-of Relief Line). In the wake of the Spadina-York extension fiasco, Toronto needs a total rethink of the business and design models used for subways. We also fear the province’s RER’s operating costs will be dangerously high if we don’t soon get serious about turning suburban GO station lands into multi-use destinations, but even on that front real estate presents revenue-tool opportunities.

We have big challenges, but we’re suddenly on a bit of a roll, exhibiting flashes of creativity and civic self-confidence not seen in a half-century. Let’s keep the momentum going.

– Stephen Wickens is a veteran Toronto journalist and transportation researcher. @stephenwickens1

– Ed Levy PEng and transportation planner, co-founded the BA Consulting Group and is the author of Rapid Transit in Toronto, a century of plans, projects, politics and paralysis

– Steve Fry is president of Pacific Links, which connects Asian, European and North American entrepreneurs and investors. His consulting work has involved infrastructure project funding in Asia. pacificlinks.ca