If you’re not bringing subways to your urban areas, you have to bring urbanity to your suburban station catchment areas. Anything else is obscenely wasteful

This column ran in the National Post on February 14, 2011. It’s business as usual with a wasteful approach to stations on the Spadina-York subway extension, but TTC vice-chairman Peter Milczyn made an encouraging announcement at the January 5, 2012 planning and growth management committee meeting. He said he will push to ensure we never again build such standalone stations.

By STEPHEN WICKENS

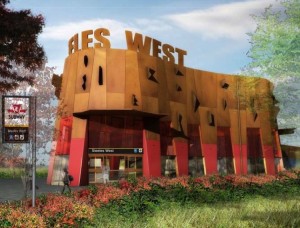

Apparently, Steeles West subway station will get a hip, downtown façade. Too bad it won’t get a real, downtown built form, hip or otherwise.

Politicians keep telling us capital and operating funds for transit are scarce, so why do we even consider standalone subway stations, let alone permit the plans and discussions about them to descend into architectural wankfests?

While we blow $857-million on stations for the $2.6-billion Spadina-York extension, many seemingly intelligent Torontonians debate the relative costs of LRTs and subways and puzzle about how some places on this planet make real rapid transit affordable and effective — even profitable on occasion.

Subways can pay for themselves in truly urban settings. We proved that a half-century ago along Yonge and Bloor streets and University and Danforth avenues. Present-day Hong Kong has turned subway building into a profitable business for all concerned.

The key is to understand and act upon the transit-land use relationship and capture the values created by rapid transit. In the 1950s and ’60s, for example, a much smaller and poorer Toronto could build subways without help from Queen’s Park and Ottawa because the existing urban form made passive value capture possible. Tax-base and ridership increases were enough.

But to make subways viable in greenfield environments and suburban areas originally designed for the car, aggressive and directed value capture strategies are needed. If you’re not bringing subways to your urban areas, you have to bring urbanity to your suburban station catchment areas. Japanese railways such as Hankyu and Tokyu pioneered these transit-oriented development models nearly 100 years ago.

In old inner-city Toronto, we had so much early urban success that we tolerated some wasteful standalone stations — though they were small and utilitarian. We should have adjusted the station and vicinity planning demands for our first forays into suburban Scarborough, North York and Etobicoke, but senior governments willingly subsidized the waste. Short-term it appeared to work, but it is one factor that contributed to the erosion of our political will to properly fund transit.

In Hong Kong, MTR Corp. builds and operates the subway system and has been profitable every year since 1979, largely because it’s also a major property developer with latitude. Malcolm Gibson, MTR’s chief of project engineering, told me seven years ago the key is that “tunnels and tracks will always be costly, but stations can be gold mines.”

To make that work, especially in a suburban environment such as the Spadina-York extension, the subway builder (that’s us, the taxpayers of Ontario) must ensure every station is located in the centre of an intense mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly node.

Because the space above the station carries the biggest premium, we must ensure the basic station — platforms, escalators et cetera — are part of the basement/foundation of a major development from the start. If you wait till the line is built and then try to sell air rights or build above a working station, huge amounts of the marginal subway-generated real estate premium is gone forever. Note that the most successful stations in Toronto have almost no footprint at the surface. They’re not monuments to “starchitect” ego.

In a North American context, the chances are beyond remote we’ll ever get subways for free, but it’s realistic to demand that developers pay for our stations. If we can’t do it, we’re putting the stations in the wrong place and/or the land-use nexus potential hasn’t been properly factored into the funding model.

Meanwhile, back in Toronto, as the march of folly continues, we get “hip facades” and irrelevant comments about the Steeles West plan from respected architects, university professors and their students.

Discuss landscaping, oxidized surfaces, the size of the lettering on the station, the latest celebrity gossip and the Maple Leafs if you must, but the one question that matters about Steeles West station is: How many thousands of people will perform daily functions such as living, working, shopping and playing within an easy and pleasant five-minute walk of the turnstiles?

Mentions of the station’s green roof and LED lighting, meanwhile, should make thoughtful environmentalists retch.