It wasn’t the top story of the day, what with details emerging about James Earl Ray’s stay in Toronto after gunning down Martin Luther King. But even with a federal election campaign moving into the home stretch, the TTC’s recommendation to Metro Council that we make our next subway-building priority a line through the core at Queen Street was front-page news on June 12, 1968.

Toronto had opened Bloor-Danforth extensions into Scarborough and Etobicoke the previous month and would break ground on the Yonge extension north from Eglinton less than four months later.

Here, in the interests of adding historical perspective to the current Downtown Relief Line discussions, we provide the non-bylined Star story from that day, with a few footnotes at the end.

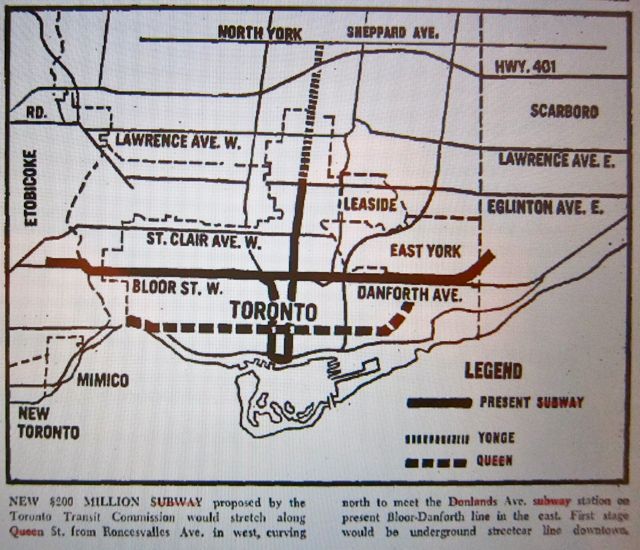

$200 million Queen subway proposed; TTC to curtail University service

The Toronto Transit Commission yesterday proposed construction of a 7.75 mile, $150- to $200-million Queen St. subway and almost simultaneously revealed it is reducing service on the already existing University Ave. subway.

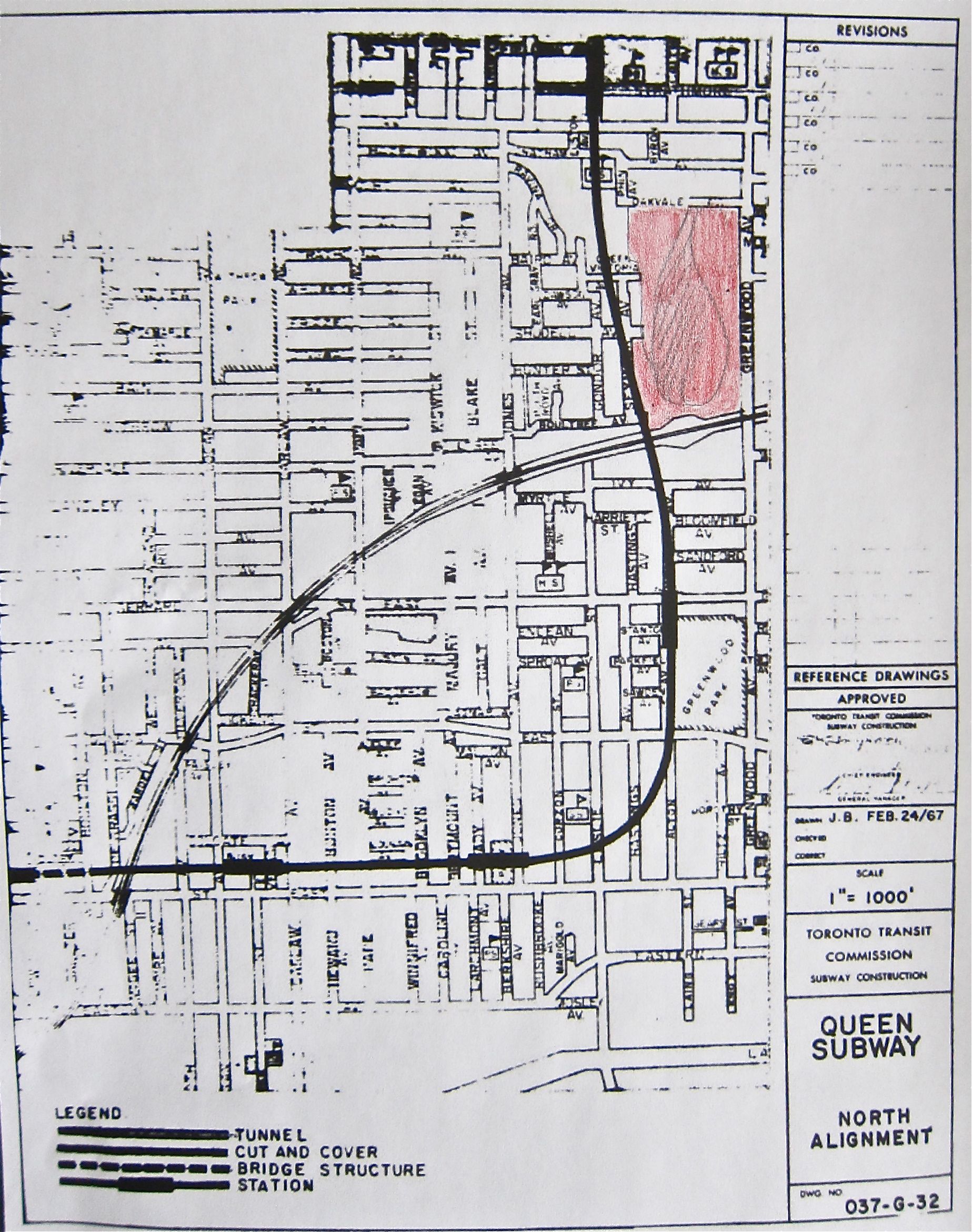

The 15-station Queen subway stretching from Roncesvalles Ave. in the west and curving north to meet the Donlands Ave. subway station on the Bloor-Danforth line in the east was proposed to Metro Council. If approved, it would probably be built after the North Yonge extension is completed in 1972. (1)

The decision to cancel University Ave. subway service all day on Sundays and after 10 p.m. on other days as an economy move (2) was apparently made in secret session some time ago and was revealed in a terse report by J.G. Inglis, general manager of operations. It is effective June 23. During the off-hours, trains will be replaced by bus service.

Mayor William Dennison estimated the move could save up to $250,000 a year in operating costs. But the TTC admitted today that the saving will be only $80,000 for the rest of this year (less $15,000 to install new signals) – and 24,000 people will have to take the bus every week.

It’s expected the reduced hours will stay in effect until eventual new routes like the Spadina rapid transit line feed more riders into the University line.

The TTC told Metro Council the first stage of the proposed Queen subway would be a $37-million underground streetcar line from Sherbourne St. to Spadina through the downtown core. The commission said this line should be built so it can be converted into a full-scale subway as soon as Metro is ready.

The Queen line is considered to be the next in priority to North Yonge, despite the fact that a rapid transit right-of-way is being built into the Spadina Expressway. The alignment of the new line would be a partial “U.”

In the east, the subway would bend north at Berkshire Ave., cut across Leslie St. and Hastings Ave. north of Queen St., follow for a few blocks an alignment along Alton Ave. to the west of Greenwood Park, then swing north to the Donlands station. Besides the Roncesvalles and Donlands stations, … See $200 million, page 4

$200 million Queen subway proposed

Continued from page 1 … there would be stations at Lansdowne Ave., Northcote Ave., Givins St., Bellwoods Ave., Bathurst St., Spadina Ave., University Ave., Yonge St., Sherbourne St., Sumach St., Broadview Ave., Logan Ave., Jones Ave., and Gerrard St. E., at Alton Ave.

The station at Queen and Yonge Sts. has already been roughed in and is below the Yonge subway. Commuters use part of it to travel from one subway platform to the other in Queen station.

The $30,000 report on the TTC’s studies came as a surprise at Metro Council. (3) Only a brief one-page letter indicated that the report, which consists of pages of functional drawings of routes, had been distributed to Metro Council members.

The plans had been discussed in secret by the commission and released directly to Metro without first being discussed in a public meeting. The TTC report, signed by Inglis and W. H. Paterson, general manager of subway construction, recommended against merely building a short underground line to take streetcars.

The two officials recommended instead that a hard look be given to a full-length Queen subway on the alignment suggested in the report.

Four possible alignments were mentioned in the report. The two officials all but rejected an alignment south of Queen St. A review of properties along the south side of Queen St. revealed that excessive underpinning and demolition would be involved, the report said.

They suggested tunnelling directly under Queen (4).

The decision to cut service on the University line was attacked by Controller Allan Lamport.

He said it would stunt Toronto growth and might ultimately cost the city more money than it would save, by creating more traffic congestion as persons who would otherwise use the subway turned to cars. Lamport said it was ridiculous for the TTC to expect people to stand out in the open after 10 p.m. waiting for a bus “in these days of violence and muggings.”

FOOTNOTES:

1. The Yonge line extension opened late and went over budget, the first time the TTC had missed a deadline or suffered cost overruns on a subway-building project. The extension opened in two phases, first to York Mills in 1973, and then to Finch the next year. (Okay, for those who quibble, the commuter lots didn’t open on time in 1968 for the Warden and Islington stations.)

2. Cost savings were increasingly a concern in 1968. Even though Metro agreed to stop charging the TTC property taxes on its real estate and even with operations turning a $2.4-million profit in 1967, staff feared it was slipping back into the red and would have to tap reserves to cover operating losses. (1968 and 1969 both saw $1.2-million-dollar losses). Tax revenue was not used to fund operations, and the TTC didn’t run deficits until subsidies first became available in 1971 (after that, it never turned a profit again).

3. It’s unlikely that the reports were a surprise to council as the report was completed and being discussed for at least 10 days before being formally presented to council in front of reporters; it was also in the works for more than two years. Metro Council also formally requested the $30,000 report on Feb. 22, 1966. The Toronto Star story indicates that the report “consists of pages of functional drawings of routes, had been distributed to Metro Council members.” The version of the “Confidential, not for publication” report on file at the City Archives (414150-1, Series 1250, File 429) appears to be missing all of the pages of drawings.

4. Tunneling directly under Queen in the core, but preferred plans included cut-and-cover tunnels or even open subway trenches parallel to Queen St. outside the core, the same way the Yonge line was built between Bloor and Eglinton. The alignment included a cost-effective connection with the Greenwood yard; current designs for the DRL to cross Danforth at Pape, are said to include a far more costly and elaborate plan for yard access (including a Y from tail tracks north of Danforth). DRL tunnels are also said to be based on a big unibore design, rather than using paired TBMs.