Nearly everything about the way the TTC is structured and governed must change if good advice, wise planning and quality transit at a reasonable price are to be priorities. Otherwise, Andy Byford will go the way of his predecessors.

Good luck Andy Byford!

Next to crime and trauma scene cleanup specialist, leading the Toronto Transit Commission is the worst job in your new home city.

The fact that your three most recent predecessors were forced out by politicians barely scratches the surface of what’s wrong with this gig. If you are the man for the job and if you dig deep, you’re sure to conclude that starting points must be a new relationship with elected officials, a new corporate culture and a total restructuring, including a spun-off entity that fosters commercial integration of transit and land-use.

Customer service panels, town halls and the addition of citizen commissioners can only diddle with the symptoms of a decades-long decline.

Yes, it was petty and counterproductive for those five commissioners to axe Gary Webster, but you’re surely smart enough to see through the political posturing, even if many seemingly intelligent Torontonians swallowed whole. You must have seen similar backstabbing and disingenuousness while working in Australia and the U.K.

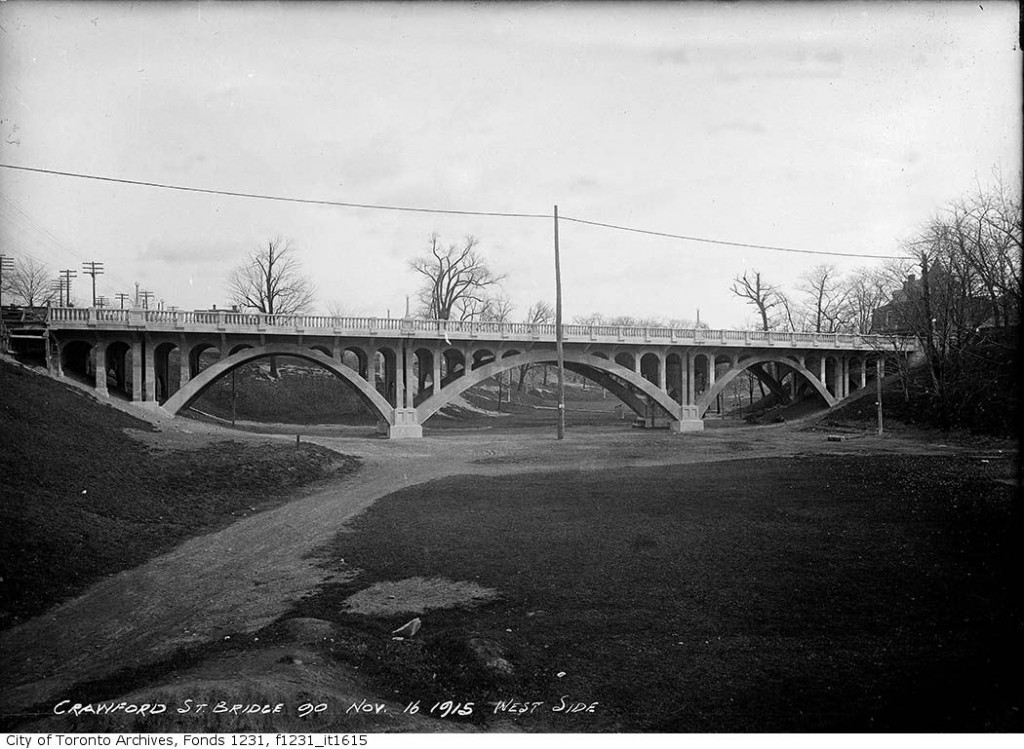

TTC managers have been pressured to tailor advice for political purposes going back at least to the 1970s, when we somehow chose to maroon stations of the Spadina subway in the median of an expressway.

Good but powerless experts foresaw woes of the Scarborough RT well before it was built. And those who felt in 1989 that we should cut our losses and scrap that line were effectively silenced.

Pressure to manufacture a case for the Sheppard subway and play down the urgency of a long-proposed line through the downtown core, beginning 30 years ago, will cast a shadow over many debates you’ll have to lead.

In fact, there’s a good case to be made that all pending plans for Eglinton, Sheppard, Finch or a northerly extension of the Yonge subway are trouble if the so-called Downtown Relief Line can’t jump the queue. (Little-known fact: tiny, cramped Yonge-Bloor station sees more daily passenger movements than Pearson airport and Union Station combined).

Of course, politics also played a big role in the rush to create the Transit City plan in March 2007, and to sell it to the public ever since. There are people still shaking their heads over a decision by one TTC manager to attend and appear prominently at the launch of Adam Giambrone’s brief run for the mayoralty.

The latest census shows Toronto has 2.615 million transportation experts. But, while many realize transit is a problem of organized complexity, most seem to prefer simplistic debate — black or white, left or right, subway or light rail. This suits our ideologically riven council members who want us to shut off our brains and pick sides. It’s also essential to mainstream media, which increasingly cater only to those with short attention spans.

But it doesn’t help anybody make wise decisions.

Compounding the mess, Andy, is that Toronto wasn’t big when the car became king. The pre-amalgamated cities of Etobicoke, North York and Scarborough have about half the density of old inner Toronto, and the gap isn’t closing. Those outer areas were designed for cars and drivers, but are now populated by people who need transit. Alas, the built form makes quality cost-efficient service delivery tough.

Our long-standing assumption that pushing subways into suburbs would automatically drive urbanization turned out to be bunk. However, attempts to get the TTC to seriously consider how to adapt and adopt creative funding models and aggressive value-capture tools, like those used in the Far East, have been met with disinterest at best (while still a city councillor in 2003, David Miller got the TTC to agree to report on transit development corporation models like the one in Hong Kong, but despite repeated requests over years, the TTC has been unable to produce evidence that it did any work on the project).

Even the mayor’s office, which purports to favour private-sector involvement, had the most interesting parts of Gordon Chong’s report on subway financing chopped before publication (make sure your copy is an early uncorrected proof containing Chapter 7, “Other Value Capture: Revenue Generation Options”).

If we truly believe transit spending is an investment, returns on the investment have to start becoming a priority. If we do that, it forces intelligent debate on the real relative costs of subways and light rail. We’re likely to still conclude LRT is the way to go in many cases, but the debate will have been honest.

Sorry if you probably know all this, but talk with your vice-chair, Peter Milczyn; he seems increasingly attuned to the possibilities and the shortcomings of our previous model.

Make sure you thank your predecessor for eventually standing up and opposing the loony idea of burying light rail under Eglinton East, but you might ask him where was he on the possibly-as-wasteful design and funding models for the ongoing Spadina-York subway extension. Deep-bore tunnels through low- and no-density areas and grandiose standalone stations make this project far more costly than it needed to be up front, while hindering the long-term development processes that can help it pay back.

Yes, some bad things happened under Webster, but overall he was just the latest fall guy for a dysfunctional organization.

For years, one of Toronto’s most revered and entertaining transit experts has been saying, off the record and only partly in gest: “The fastest way to find yourself unemployed in this town is to speak the truth.”

Some part of that wisdom will always be true.

You’ll have to choose your battles, even in your interim role. But unless you get extremely wise help to start radically altering the rules of the game, you’re guaranteed to lose – as is Toronto, again.