By STEPHEN WICKENS

“To offer riders a more convenient route and alleviate potential budget pressures …”

Leading with those words, provincial transit agency Metrolinx issued a news release justifying the Ontario government’s decision to kill the Hurontario light-rail line’s two-kilometre loop through downtown Mississauga.

It’s hard to argue with a declaration that the most attractive routes at the best possible prices are a priority, though the degree to which this adjusted plan is likely to succeed in Mississauga prompted considerable debate – debate that continues even if it has since been drowned out by news (on March 26, 2019) that Premier Doug Ford has decreed big changes are in the works for four Toronto transit projects.

Some are still questioning how the changes to the Hurontario plan can be more convenient for people whose journey includes Mississauga Centre – surely a major proportion of potential ridership. At least the line is to be built in a way that allows the loop to be resurrected later.

As for cost savings: Although the line is now to be 10-per-cent shorter with three fewer stations, the estimate remains $1.4-billion, same as in 2014, meaning “budget pressures” is basically PR-speak for cost overruns, even if the “project scope” has changed. The overruns are mostly the result of “important design and engineering needs” not identified until 2017, Metrolinx spokeswoman Amanda Ferguson said in an e-mail.

Fair enough. Let’s hope everything pans out better than advertised.

But if Mr. Ford and his transit advisers really are serious about “more convenient” routes and alleviating “budget pressures,” the obvious starting point would have been big changes in Scarborough, and not by adding stations to the ill-conceived subway project.

At a time when the government is rightly making noise about deficits and debt it inherited, plans for extending the Toronto Transit Commission’s Line 2 and the eastern stretches of Mayor John Tory’s SmartTrack plan have us on track for a double-whammy of spectacular waste and suboptimal services.

There has long been a much better plan, and Mr. Tory knows about it.

It’s an option that should have appealed to the Premier in that it doesn’t involve LRTs or reverting to the nearly fabled seven-stop light-rail route that is an article of faith in some circles, including on the opposition benches at Queen’s Park.

Scarborough does deserve much better than its faltering SRT line (foisted on the TTC in the 1980s by a previous provincial government). And, fortunately, the groundwork for the better plan has been salvaged with the Ford government’s apparent willingness to largely continue with Metrolinx’s Regional Express Rail network (recently rebranded “GO Expansion”). In simple terms, GO-E adds track capacity on most Metrolinx corridors, with more stations and, probably, electrified operations that permit much more frequent service.

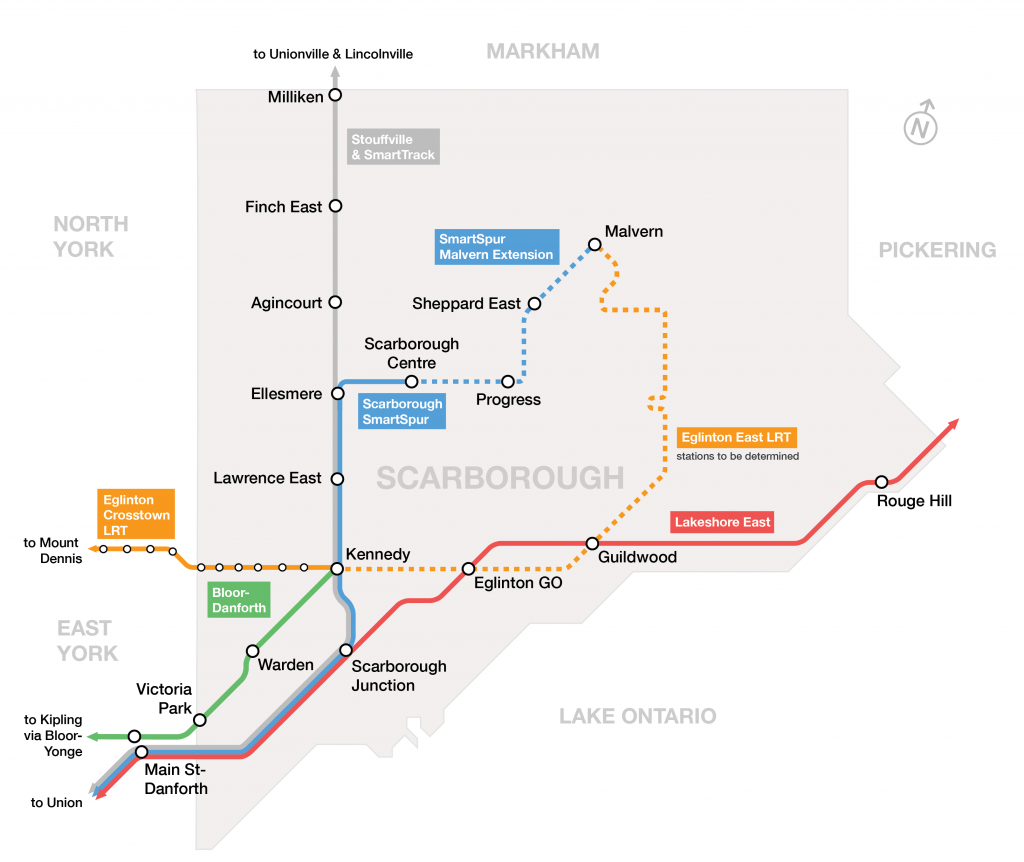

Conveniently, one of those corridors – the one serving Markham and Stouffville – passes less than 1.5 kilometres from Scarborough Town Centre. As a bonus, much of the land needed to build a spur line between STC and GO’s corridor is already publicly owned. If we let GO serve Markham and divert SmartTrack service to STC, we don’t need to tunnel a six-kilometre subway for $4-billion, or $6-billion or more.

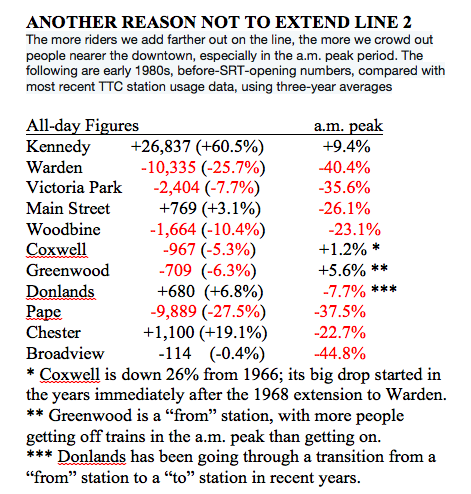

Better still, transit users would get a faster, more direct trip downtown from Scarborough than they would by subway – seven stops to Union in one seat, rather than 22 with a change of trains at perpetually overcrowded Bloor-Yonge station. In fact, SmartSpur would allow SmartTrack to relieve a bit of the crowding on Toronto’s subway, rather than aggravating it as the current Line 2-extension plan would.

The SmartSpur idea first showed up in a 518-page report about electrifying GO’s rail system, released in 2013 by Transport Action Ontario (a volunteer group that, among other things, lets transit professionals do work other than what’s assigned in their day jobs). It was a serious plan produced and reviewed by serious transit people. The biggest knock against it has been that it kills any case for a Scarborough subway extension, which was little more than a vote-buying promise that underpinned former premier Kathleen Wynne’s support for Mr. Tory in the 2014 mayoral race (against Mr. Ford).

SmartSpur is based largely on the fact that upgrades – already under way – to double-track the Stouffville corridor and add a fourth track to the Lakeshore East line offer far more capacity than GO needs. Twenty trains an hour on the corridor, when it only needs four to serve Markham. Running subway-like frequencies, the remaining 16 trains an hour, will require a state-of-the-art signalling system, not cheap, but overall potential savings were estimated to be in excess of $2-billion, and that was before the subway-option’s tunnelling and station cost estimates soared.

We know the Premier prefers underground trains (and is talking now about going underground on Eglinton West, too), but his advisers should have pointed out forcefully that the cities getting transit built – the great metropolises with those enviable subway maps – rarely bore costly tunnels beyond their dense downtowns (55 per cent of London Underground is above ground, as is 62 per cent of Hong Kong’s system).

Going the SmartSpur route offered Mr. Ford a dual opportunity: to tackle an embarrassingly wasteful commitment made by the former premier, while showing his former mayoral-race opponent, Mr. Tory, how to do SmartTrack right.

Whether the Premier is big enough to backtrack now is an open question, as is whether Mr. Ford is receiving quality advice.

He could still look like a genius in Scarborough, reinvesting savings to push SmartSpur out to Malvern via Centennial College, or extending the Eglinton Crosstown east from Kennedy. Of course, Mr. Ford could also reallocate funds to a Relief subway, the most urgent transit need in Toronto and the GTA.

As for Mississauga, maybe Mayor Bonnie Crombie can persuade her city to fund its loop. Toronto had to pay for its subways when it was still building them downtown.