Once upon a time, a much smaller and poorer place called Toronto went ahead and built subways without any funding assistance from Ottawa or Queen’s Park

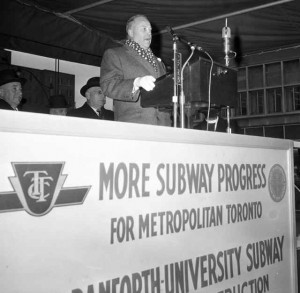

This story first appeared in the Toronto Star on Feb. 3, 2012. All photos were taken by Toronto Telegram photographer Peter Ward and are published here courtesy of the York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections.

By STEPHEN WICKENS

Torontonians have seen countless transit plans in recent years, but even the wildest fantasy versions haven’t considered time travel — and maybe that’s a shame.

If we could all hop a Red Rocket to Nov. 16, 1959, and get off at University Avenue and Edward Street, we could witness an event locals might consider unbelievable. And if planners and politicians were among the time travellers, local transit talk might be more relevant and productive, even before the ride back to 2012.

***

The guy in the ill-fitting red hard hat operating the steam shovel for the sod-turning ceremony is Leslie Frost, premier since 1949. Mayor Nathan Phillips is among the dignitaries, along with “Big Daddy” Fred Gardiner, the Metro chairman who would prefer that expressways get priority. Allan Lamport, a former mayor who successfully argued that subways would be a better long-term investment, will take a turn with the earth-moving equipment after Frost is done.

Observant guests from the 21st century might note the absence of any giant cheque for the photo-op. And there is no spin-doctor’s slogan on a lectern placard, no printed backdrop screens lauding Queen’s Park for creating jobs or tackling gridlock. Of course, Frost has good reason to not blow his horn: he doesn’t bring a penny to the project. Instead, he delivers only a speech, a stern warning to municipal politicians that they’re on their own, that they’d better not get mired in debt for this $200-million University-Bloor-Danforth subway plan — 25 stations over 16 kilometres.

***

By now, you know the job got done, and it was accomplished on budget in just six years and three months.

“It was a remarkable feat,” says veteran civil engineer and consultant Ed Levy, who has written a forthcoming book on Toronto’s transportation history. “It took guts to go ahead without provincial funding, especially when you consider this was a much smaller and poorer city, and tunnelling technology was relatively primitive.

“The truth seems unbelievable today, after decades of paralysis and sickening blunders on the rare occasions when Queen’s Park has provided funding.”

In 1959, it had been five years since the original Yonge line from Union to Eglinton had opened (funded largely by fare-box surpluses) and Toronto was eager to get building again, even if the province wouldn’t help.

To figure out how we did it, Levy says several factors must be considered. We were willing to put a surcharge on property taxes, though the towns of Mimico and Long Branch objected. But the biggest factor is almost certainly that “the economics are pretty well guaranteed to work when you put subways in the right places ” — already dense, transit-supportive parts of the city.

“We don’t have a lot of that and, obviously, we can’t build only downtown, but it was madness to stop building subways in old Toronto in the 1960s,” says Levy, whose first engineering job involved plans for shoring up buildings for the University line tunnels.

“Look at cities that have been able to keep expanding; they’ve all built steadily from the middle out. London’s tubes go a long way out, but all go through the core. [And though few tourists may realize it, 55 per cent of London Underground is actually above ground, and when Toronto was good at building subways on time and on budget, we went open trench through low-density areas north of Bloor on the Yonge line, or above ground once the subway rolled into Scarborough at Victoria Park.]

“We might yet be able to make the economics work in the suburbs, but it will take big changes to our whole approach, lots of up-zoning and big increases in the densities of those areas.”

Fifty-five per cent of the tab for the University and Bloor-Danforth lines came from property taxes levied by Metropolitan Toronto, a senior local government abolished in the 1998 amalgamation. The Toronto Transit Commission, which didn’t need taxpayer subsidies for operations until the early 1970s, was profitable enough under its zone-fare system and a primarily urban operations area to pay 45 per cent. Eventually, under Frost’s successor, John Robarts, Queen’s Park guaranteed a $60 million loan, allowing a work speed-up that saw the line from Woodbine to Keele open in 1966 rather than 1969.

Can hiking property taxes make a difference?

The Toronto Board of Trade estimates we’d get only $22 million a year if we raised residential rates 1 per cent, but considering most people in 905 pay at least 25 per cent more in property taxes, it may be an option.

Transit advocate and blogger Steve Munro says one thing working against us now is that all construction costs have risen faster than the rate of inflation. It’s tough to quantify this, but he appears to be correct. The Bank of Canada says $200 million in 1959 is worth roughly $1.6 billion today, and there’s no way we could build those lines and the Greenwood maintenance and storage facility for the latter figure.

“We also used cheaper cut-and-cover box tunnels, rather than the current deep bore approach,” Munro says. “The stations were rudimentary, often with only one exit. It also didn’t hurt that, 40 years earlier, people thought long-term and built that lower deck on the Bloor viaduct, not that anyone would have considered tunnelling under the Don River in the 1960s.”

But Munro, like everyone else interviewed for this article, comes back to the relationship between land use and transit and the need to reconnect mutually supportive forces if we’re ever to make costly infrastructure pay and keep expansion ongoing.

“Some will argue that, ‘You don’t see lots of towers along the original Bloor-Danforth,’” Munro says. “But it worked because transit demand was already well-established for kilometres north and south of the new subway. The street could probably use redevelopment now, but it serves as a great example that effective urban form doesn’t have to include high-rises.”

Transport and energy consultant, author and former city councillor Richard Gilbert made a similar point in a 2006 paper titled “Building Subways Without Subsidies.” In it, he calculated a combined 30,000 to 40,000 jobs and residential units within a square kilometre of each station on the $2.6 billion Spadina-York subway extension would allow it to pay for itself in 35 years.

“You could do all that without going over seven storeys,” he says, adding there has been little development on the Spadina line in 35 years of operation. This extension into York shows few signs of paying back any better. People have to understand that subsidies are a substitute for density, and that’s fine if money is no object,” he says. “We’re making the same mistake again on Eglinton. We’re blasting more than $8 billion at it and the province hasn’t set any performance-based conditions. There’s not a single requirement about density around and above the stations.

“If we don’t fix this, if we don’t put some real effort into figuring out how the public can get back even some of this money, we have no hope of obtaining real value for the $50 billion Metrolinx is supposed to spend on the Big Move.”

Eric Miller, director of the Cities Centre at the University of Toronto, says “we’ve been fooling ourselves for decades” with the idea that development and urbanization will automatically follow subways in places first developed around the car.

“It was always a well-crafted myth that the TTC and others generated,” Miller says. “Building heavy rail is a necessary but not sufficient condition to generate high density in the suburbs. We have to get really serious about ensuring that density, walkability and rich mixes of land uses happen and we can’t waste time.”

In January, TTC vice-chair Peter Milczyn made an encouraging but generally unreported announcement at the city planning and growth management committee meeting. He said he and TTC chair Karen Stintz would work to ensure all future stations had at least some development upstairs from the start. But some see this and initiatives such as Metrolinx’s Mobility Hub concept as mere timid steps in the right direction; that small islands of urbanity in ever-growing seas of car dependence won’t do and that the full costs of sprawl must be identified and recaptured.

John Sewell, former Toronto mayor and author of The Shape of the Suburbs, argues the entire GTA had better come to grips with the urgency because Metrolinx’s investments in the 905 area are even less likely to pay for themselves than the subsidy-driven services we pushed into the older 416 suburbs beginning in the late 1960s.

“The GTA has to compete globally, and we’re guaranteeing ourselves negative real returns on a grand scale,” Sewell says, adding the financial burden will almost certainly further erode long-term political will to properly fund transit, even in places where transit is cost-effective.

“Because of the way we’ve built the outer suburbs, any type of transit we put out there will require massive subsidies for operations,” Sewell says. “That’s the problem with suburban form; sprawl is unsustainable — literally, financially unsustainable. Mississauga is just learning this now.”

Planner Ken Greenberg thinks our slide into bad habits began even before the Bloor-Danforth opened. “One great mistake of that era is that we started detaching land use from infrastructure investment. On Yonge, at St. Clair, Davisville and Eglinton, you have, in effect, little cities. Lots of people live and work near those subway stops. For the most part, such is not the case on the Bloor-Danforth and Spadina. Something was suddenly and fundamentally off kilter and it took Toronto out of the realm of what other cities have been doing consistently.”

Levy and Gilbert also point to other trends that were developing by the late 1960s. “People will be irritated by my saying this, but our transit problems began when the suburbs began dominating at Metro,” Levy says. “Some of it may be coincidence, but the loss of the zone fares and the way Scarborough, Etobicoke and North York developed means subways may never pay for themselves there, and Vaughan is another story altogether. They don’t have the density, but they have the votes.” [The Toronto-East York community council area, 6,348 people per square kilometre, is more than twice as dense as Scarborough and Etobicoke, and 63 per cent denser than North York.]

University of Toronto historian Richard White makes the case that suburbanites did contribute because a building boom in Scarborough, Etobicoke and North York made the Metro tax surcharge particularly lucrative, but he agrees the suburban form in those former boroughs and the end of the zone-fare system made public transit expensive.

Gilbert, former research director at the Centre for Sustainable Transportation, says even the much-pined-for funding formula started in the 1970s by former premier Bill Davis — a 75 per cent subsidy for new infrastructure and 50 per cent toward operating deficits — probably worsened our problems long-term. “Those subsidies obscured the true cost of providing urban transit in suburban places, so it’s no surprise that they keep getting larger. This is a classic case of a perverse subsidy.”

That brings us to planner Pamela Blais, who has spent at least 15 years studying how hidden “perverse” subsidies encourage sprawl much more effectively than planning guidelines and growth boundaries fight it. But the author of Perverse Cities makes clear she would prefer bigger transit subsidies from senior governments because the public service role justifies them.

She says that if we want to get on with building transit infrastructure and delivering good service across the GTA, we must address the fact that the lower the density and the more we segregate land uses, the more expensive it is to deliver all network services, and that includes gas, hydro, mail, sewers, water, and telecommunications.

“When everybody pays the same average price, rather than the marginal cost of service provision, people in the densest areas overpay to subsidize people further out, where they largely don’t pay their fair share. Trying to outlaw sprawl won’t work, but if we properly identify the hidden cross-subsidies and get the pricing signals right, people will make the right decisions,” she says, citing development charges and the market-value assessment approach to property taxes as areas in need of reform.

Paul Bedford was Toronto’s chief planner when the city produced its first official plan after amalgamation, and linking transit and land use was central to that mission. He hopes we can find “consistent leadership over time, so plans don’t keep changing with each municipal election.

“The other key is that the Metrolinx development strategy has to be really bold, not just with planning new infrastructure, but with funding sources for operations and maintenance,” says Bedford, who is still waiting to learn if he will be reappointed to the Metrolinx board. “We need the funding plan this year,” he says, adding he thinks plans for a downtown subway should be moved up the priority list. “We’re at least 30 years behind, and we’re going to be adding the equivalent of Greater Montreal in the next 25 years. Heaven help us if we allow much of it to be car-dependent sprawl.”

But Greenberg points out that sprawl is marching on. “Yes, we’re having trouble getting transit infrastructure built, but our problem is more land use than transportation,” he says. “We’re getting some intensification in a few places, but go to King City or Uxbridge, places like that on the fringes, it’s still ongoing, full, industrial-strength, traditional sprawl. More and more people living in environments where they have no practical choice but to drive everywhere. We have policies intended to fight it, but way too many incentives to continue as is. We’re sucking and blowing at the same time and the illusion is that we’re wealthy enough to afford it.”

Sewell, meanwhile, is skeptical that we can remake the suburbs. “It’s really hard to retrofit any place built for the car, they haven’t been evolving into urban places. If it’s going to work, it’s going to take a lot more than density. We need that real mix of land uses and short blocks. Planners have to keep the pedestrian in mind at all times and we need the financial incentives.

“If it’s going to happen, it’s going to take a really long time and I don’t know that we have it. Maybe if we took that train back to 1959 we could warn them, but I don’t know if that would help, either.”