By STEPHEN WICKENS

On Monday, eight days after the end of the world, a Toronto TV newscast was still making a fuss about the shutdown of a Gardiner Expressway ramp that had been, until April 16, funnelling 21,770-plus vehicles onto York, Bay and Yonge streets on average weekdays.

“Car-mageddon” forecasts began in earnest on Feb. 8, with Mayor John Tory making a stern, brows-knit announcement. “I’m not going to sugar-coat this,” he warned, conjuring memories of newsman Ted Baxter from the old Mary Tyler Moore Show.

In March, Wheels, the Toronto Star’s largely advertorial automotive section, published a rant under the headline “York-Bay-Yonge ramp demolition will equal traffic chaos for downtown Toronto.”

Then, in the final days before the Y-B-Y ramp closed, local media outlets revved up the coverage – lots of interviews with concerned and angry expressway users interspersed with bureaucrats explaining that the ramp is 50 years old and crumbling.

One official, apparently unaware that relatively few of Toronto’s downtown workers arrive on the eastbound Gardiner, said “we’ll all just have to bite the bullet.”

I hate sitting in traffic as much as the next guy, (part of the reason I rarely drag tons of steel, glass, rubber and plastic with me when I go downtown). I own a car and I’m sympathetic with co-workers made late by congestion. I very much appreciate that there’s a significant group of people whose livelihoods require they drive into and out of the core.

Yet for all the media coverage, I haven’t seen a story that puts into context the degree to which closing this two-part ramp will crimp the transportation network during the eight months needed to build the replacement exit at Simcoe (apologies if I missed it).

After a few emails, phone calls, a little Googling and some rummaging through the home-office filing system, I’d classify the ballyhooed ramp-gridlock-crisis story as much ado about relatively little. Rather than chaos, what I see is merely more evidence of just how self-defeating car-based transportation is as a major mode in an urban context.

City staff tell us 1,537 cars were using the old ramp in the busiest 60 minutes of the a.m. rush on an average weekday. That’s less than a quarter of the average number of people who emerge downtown from each of the TTC’s seven core subway stations (Dundas, Queen, King, Union, St. Andrew, Osgoode and St. Patrick). The seven-station peak hour total is 43,295 arrivals (28.2 times the ramp number) (1).

Over the three-hour a.m. rush, the Y-B-Y ramp sees roughly 4,500 vehicles (2), while each of the seven core stations averages 14,910 people. That’s 104,352 total, 23.2 times the ramp number.

Looking at the 24-hour period, the ramp’s 21,772 total is less than any of the seven aforementioned stations (even though the subway is shut for about four hours each night). The seven-station total is 412,472, or 18.9 times the ramp number.

Not including GO and Via, 6.9 times more people get off at Union station’s subway platforms in the a.m. peak hour than the number of cars passing through the ramp. In the 20 hours that the Union subway platforms are open, they handle 118,446 people, 5.4 times the number of vehicles using the ramp over 24 hours.

And none of this includes the roughly 89,000 who travel downtown by GO Transit on an average weekday (3), or the tens of thousands more who arrive by TTC surface routes, on bikes and on foot.

In fact, as urban planner Gil Meslin (@g_meslin) tweeted in response to this post: “That peak-hour ramp usage is less than the number of people disembarking from one full GO train at Union Station.” A GO train can carry 1,670 people.

(And we haven’t even mentioned the TTC’s two busiest stations, Bloor-Yonge and St. George, neither of which is really in the core. Bloor-Yonge, BTW, handles 18.3 times as many people a day as the Gardiner ramp and, by one measure, more daily passenger movements than all of Union Station and Pearson Airport combined).

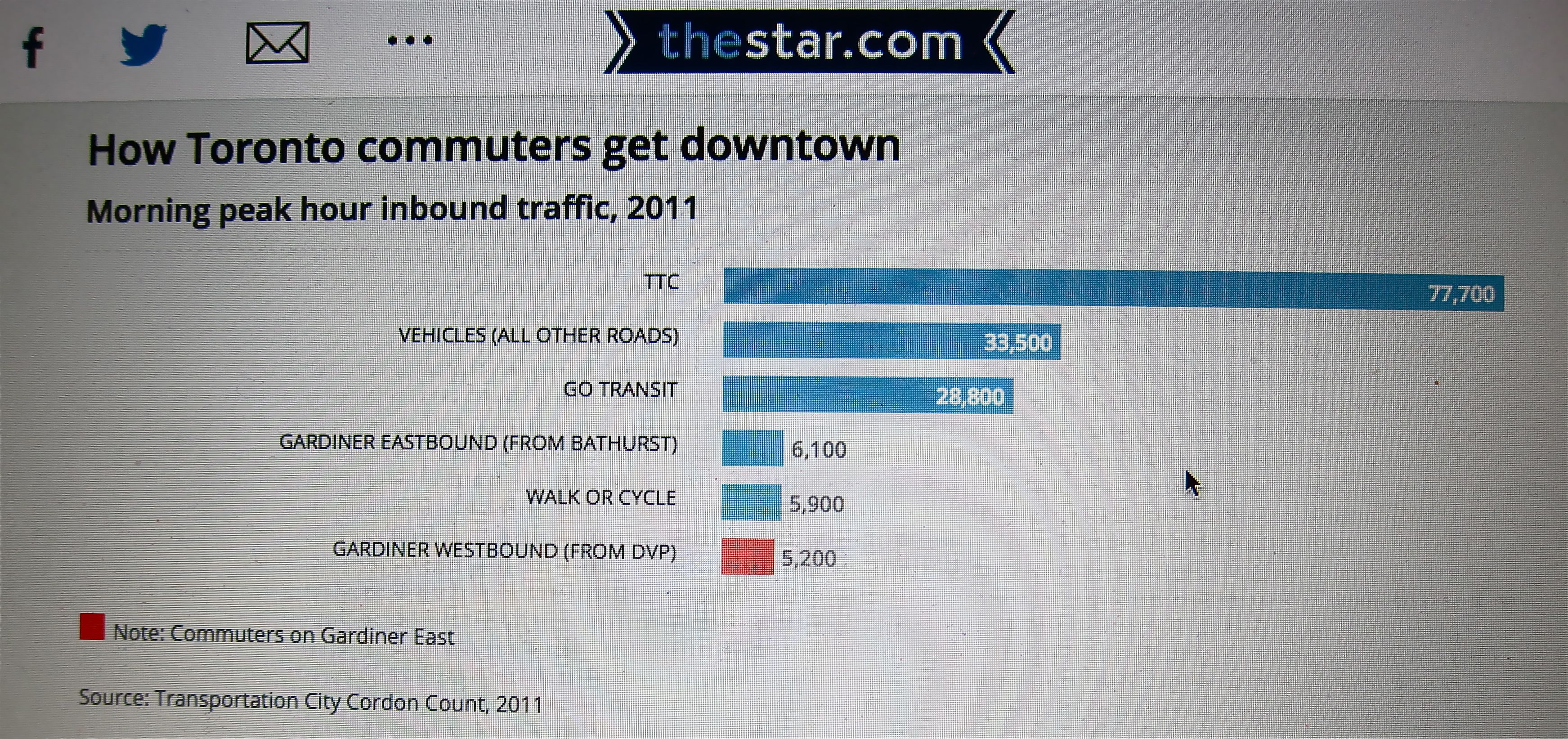

City data from 2011 measuring how people are getting downtown in the a.m. peak hour indicate that just 3.9 per cent are arriving on the eastbound Gardiner and the expressway as a whole is delivering just 7 per cent. Cyclists and pedestrians were at 3.2 per cent, and with the dual booms in condo construction and cycling those modes have likely since surpassed the eastbound Gardiner’s proportion of the total.

Would media go this big if TTC had to temporarily shut a core subway station or GO was forced to remove a handful of train runs? Highly unlikely.

Over the decades, most of the city and its media have become inured to the core transit system’s overloading. Delays happen and people get mad but public transit is resilient. As long as we’re not totally shutting down what little subway infrastructure we have into Toronto’s core, we always muddle through.

So why the big deal over a single highway ramp?

Driving is so land-consumptive that you don’t need many cars to create serious congestion. Driving is also inefficient because it’s disrupted so easily, whether by regular volume, common fender-benders, basic maintenance and construction … or the occasional ramp shutdown.

And our media outlets, including many of the reporters and editors they employ, seem unable to see differences between the urban and suburban parts of the metro area, or even within the 416. Prevailing assumptions about the importance of cars to the older parts of the city, where so much of the economic engine resides, are wildly inaccurate.

We decry the billions of dollars that congestion is said to cause us, but through ignorance and cynical politics we continue to give priority to spending on a mode that guarantees congestion and inefficiency.

Thankfully, we don’t have room to widen roads in the city. But unfortunately, politicians – even conservatives who claim to be respectful of taxpayers – choose not to listen to facts or do the basic math when it comes to urban and suburban transportation issues. And our media, especially broadcast outlets, don’t put much effort into helping to seriously inform the public.

The result is that, to ensure we don’t inconvenience a small number of vocal drivers who have the ear of media and politicians, we’ve allotted $3.6-billion for rebuilding and adjusting the alignment of a short stretch of the Gardiner Expressway, yet we somehow still have nothing for a decades-overdue subway line through the core that can benefit the city and the entire region on a scale few can comprehend.

NOTES

1. The numbers of people arriving by car are surely higher than the number of cars. I’ll factor that in and adjust the totals when the city provides it’s updated formula. I asked last week, but so far no luck. From my files, city staff acknowledged at a Canadian Urban Institute event in 2005, that it assumed cars on local expressways carry less than 1.2 people during the a.m. rush and slightly less than 1.1 for the rest of the day.

2. The city suggested I multiply by three the 1,537 a.m. peak number to get the full a.m. rush total. I’m reluctant to do that because the shoulder times outside the actual peak hour will necessarily be less. If, for example, I multiplied the TTC’s a.m. peak numbers by three, the totals for the seven core subway stations would jump considerably. I went with 4,500, which is also what The Globe’s Oliver Moore did on April 15 (page M3, but apparently not online).

3. GO buses, of course, use the expressway system, though they are a tiny part of GO’s Union customers. Vanessa Barrasa of Metrolinx told me that, “In anticipation of the Yonge-Bay-York ramp closure, GO bus made some minor adjustments for trips arriving from the west. We have not had any major delays caused by the closure.”