Our traditional approach to public real estate, especially properties at our major transit stations, involves giving away huge amounts of value to private developers (or wasting it on surface parking), while world leaders are working to master land-value capture and land-value trade relationships.

By STEPHEN WICKENS

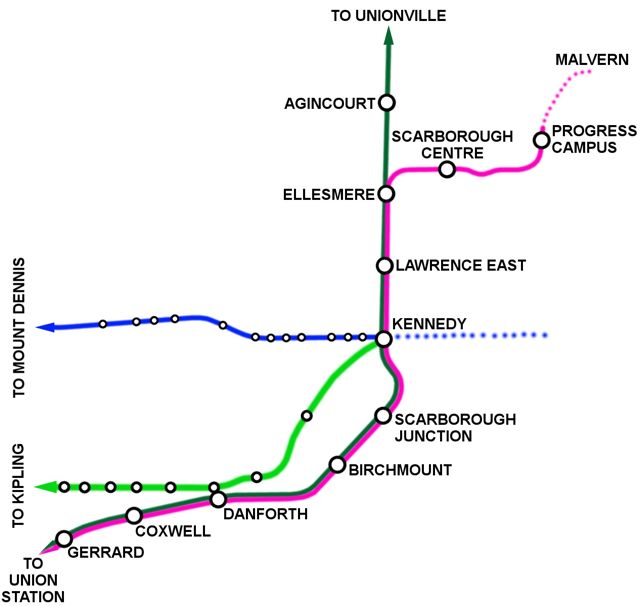

What if First Gulf controlled the land surrounding Kennedy station, 25 publicly owned acres that for decades have been served by subway, SRT, GO trains and multiple bus routes. It’s a site whose potential value has soared recently, what with the Eglinton-Crosstown LRT to open in a few years and a reasonable likelihood a Scarborough subway extension and the Mayor’s SmartTrack will roll too.

Add in tracts of nearby, largely undeveloped private lands, and the Kennedy site’s size rivals First Gulf’s Unilever (now renamed East Harbour), which sits behind various moats – river, highway, rail corridor, monolithic land uses and long blocks. Unilever might eventually get lots of transit, but even if Broadview is extended south and a bridge to the West Donlands is added, stitching that site into the urban east-downtown fabric effectively will be a massive challenge.

The comparison’s timely because one site needs urgent attention – and despite media coverage and city hall chatter, it is not Unilever. Kennedy was the natural site for a “downtown” or “centre” in Scarborough and transformation on several levels should be inevitable: It already has one-seat rides to Union, Bloor-Yonge, Scarborough Centre and Markham Centre, and soon will offer one-seat rides to Yonge-Eglinton and the airport. But it’s a hub without a champion. It lacks institutional support or gainfully employed minds offering vision. Shame on us, not just our politicians, bureaucrats and media.

Aside from an opportunity for profitable development to partly offset infrastructure costs and boost ridership enough to justify costly rapid transit priority for low-density Scarborough, Kennedy could pay back for generations if it’s the place that finally gets GTA decision-makers to understand public real estate in ways that underpin sustainable funding for the world’s leading urban transportation entities (almost all in east Asia).

But time’s running out at this hub: Options disappear every time politicians make absurd promises and every time Metrolinx and the TTC award contracts. The greatest urgency stems from the fact that plans still call for the Crosstown to dive underground at Ionview Road, nearly a kilometre west of Kennedy station. Tunneling made sense when the LRT was to swing north into the Scarborough Rapid Transit corridor and functionally replace the SRT as our de facto subway extension to Scarborough Town Centre – albeit with transfer for Bloor-Danforth riders. But although one-seat service to STC by subway now looks like a lock, station plans weren’t adjusted.

Short term, keeping the LRT on the surface and scrapping the tunnels saves us far more than the roughly $85-million the city owes Metrolinx for wasted work since council dumped the old LRT plan in 2013. Long-term, we’ll end up extending the Crosstown east and keeping the LRT on the surface from the west also eliminates the need for costly tunnels to the east. In fact, if we extend the LRT east, kill the tunnels and use SmartSpur (a plan with so much potential that those who promised the Scarborough subway have forbidden city staff from studying it properly) to connect with STC, we’d be able to eventually use a shorter more efficient route than any subway option planners have studied recently – if or when we can ever honestly justify a subway extension.

But the biggest long-term benefit will come if Kennedy station’s real estate can catalyze a long-overdue revolution in North American transit funding and planning. Kennedy’s special: We own the land; we can be that greedy developer reaping the profits. This is the basis of rail-plus-property, a business model that has played a huge role in making Hong Kong’s transit builder/operator a profitable company for 35-plus years (even if it isn’t perfect and people kvetch about transit there, too).

Historically, in Toronto, we give away land-value premiums to those who own sites near stations, some of which is unavoidable (we also twist transit plans and grasp for logic to justify alignments that mostly serve influential private interests and pension funds). MTRC of Hong Kong, trades its infrastructure spending for land-value through development and property management. Yes, we know Hong Kong is denser and their land-ownership regime is different, as are public-consultation sensibilities. But the big lessons of MTRC’s model can apply here if we’re smart enough in how we adapt the governance.

A huge but largely overlooked hurdle in our planning process is our lack of a publicly controlled entity for managing our transit-related real estate, working within a private-sector set of precepts to maximize its worth. This entity needs an empowered seat at the table from the earliest transit planning discussions and must be free to operate at an arm’s length from politicians and even transit operators. Rail-plus-property cannot remedy all our process flaws, but in its basest form it would generate significant revenue to defray capital costs, help us expedite operating efficiencies and earn the goodwill needed to allow those with taxing powers to use “funding tools” and “revenue tools” considered politically risky.

So if rail-plus-property is such a no-brainer, why haven’t we acted? We’re a riven town, trying to tame a political whipsaw. The right and some foolish mayors, going back at least a decade prior to amalgamation, have damaged the land-value-capture concept with laughable promises of free subways. The ideological left, meanwhile, tends to be fearful of anything that smacks of public-private partnerships, willfully ignoring how some competing international metropolises are getting things done. In 2003, the TTC was asked to study rail-plus-property (councillor David Miller got a motion passed at my urging, but the study was quietly ditched when he became mayor). Provincial and city reports on funding strategies in recent years have demonstrated a thin understanding of LVC. An August 2013 discussion paper commissioned by Metrolinx was somewhat encouraging (though hopes there are waning since the provincial entity quietly shut down its business-case department in the spring of 2016).

Recent off-the-record discussions with sources indicate some of our bureaucrats are waking up, though for now, we continue to rip ourselves off. We talk about transit being an investment, forgetting that real investors aggressively seek ROI.

Viewed through a rail-plus-property lens, current plans for Kennedy would have us asking:

– Why does the TTC cling to the quaint but expensive notion that stations are costs while cities capable of continuous building increasingly view them as revenue properties with trains rolling through the basement? At Kennedy, our thinking manifests itself in an unsubstantiated assumption that there’s net benefit in retaining a big bus terminal, even though it’s an impediment to transit-oriented development on a site that needs TOD. It makes even less sense if you consider that when the LRT is extended east, we won’t need a bus terminal at all.

– Why tie up swaths of valuable real estate for surface parking? The 1,000 or so spaces at Kennedy allow us to fill the equivalent of just one subway train for one round trip per day. Parking can and will be replaced in other formats via redevelopment – if it makes economic sense within a mix of uses that could include offices, shops, condos, schools, public services and recreation facilities. We need destinations around and atop our stations, a doubly crucial lesson for land-rich Metrolinx to learn, especially now that it should be preparing to strategically offset soaring operating costs from the Regional Express Rail all-day, two-way service promise.

– What thought is going into creating easy and pleasant pedestrian links between the Kennedy station zone and the surrounding areas? We think a lot about bus connections, a very good thing, but subways work best when the pedestrian is king of the catchment zones.

– Why aren’t the surrounding private land holders prominent in discussions at this end of the transit planning? Has there even been a public Kennedy station precinct planning process? Given the right lattice of incentive and disincentive, private developers will eagerly help us earn returns on investments and assets.

So, where are our bureaucrats?

Actually, contrary to popular misconception, most are at least okay. In Year 5 of his term, I’m concluding Andy Byford was probably a good hire and he seems to understand much of what I usually prattle on about. But he’s rightly focused first on turning around the TTC’s operating culture. He has some good people working for him on the capital planning side, but the parameters on their thinking appear to be constricted by assumptions desperately in need of re-examination. They lack the tools and direction required re-earn the public’s confidence (some TTC staff come across as chastened, bracing for further hits on the Spadina-York extension cost overruns and hugely wasteful standalone stations).

People at city planning have been good to talk to in recent years and seem to be awakening to the fact that established approaches are inadequate for such issues of organized complexity. Some seem to see the need for an entity that can wisely manage public land assets in the quest to make good on some of the excellent aims of the official plan, now more than a decade old (though spring-summer 2016 developments on the Scarborough subway front indicate the politics is trumping logic).

And the city is doing a real estate review, but the discussions seem to be on the overly secretive side.

Metrolinx dipped a toe in the waters of sanity by auctioning off Crosstown station sites – prior to excavation, no less – (though we’re hearing the first wave of RFPs were so restrictive that developer interest was disappointing). More disappointing is that rail-plus-property has apparently disappeared from the radar after recent behind-the-scenes moves that cost Metrolinx some of its brightest staff members.

So, again, imagine that First Gulf owns this Kennedy site, which may one day rival Union Station for the best, rapid-transit-served location in the GTA. At Unilever, First Gulf talks of 50,000 jobs and development investments worth $6-biillion (and let’s hope it succeeds). It’s obvious that First Gulf has worked hard to get the ear of the mayor’s office, just as Oxford Properties has at Scarborough Centre.

Maybe we, as a voters and residents, should try to do the same.