This item was first posted at City Builder Book Club, where you’ll find lots of great posts about chapters from Jane Jacobs’s 1961 classic, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Visit and read, and get out and walk. Go on a Jane’s Walk http://citybuilderbookclub.org/2012/03/stephen-wickens-on-the-need-for-small-blocks/

By STEPHEN WICKENS

Apart from a brief post at Torontoist, the erasure of Roy’s Square for the 1 Bloor condos went unmourned. And two stops down the Yonge subway, the Aura condos rise, snuffing hopes of those who cared that a block of Hayter Street was shut in 1978.

The Death and Life of Great American Cities has been around 50 years and Jane Jacobs has been gone more than five, but ‘The need for short blocks’, the second of her four conditions indispensable for generating diversity, remains overlooked.

On Condition 4, density, converts abound, though understanding is often dangerously simplistic. It’s tough to gauge how we fare on No. 3, but mingling buildings of different ages is widely discussed. As for No. 1, land-use mixes, there has been progress, though it will remain limited till people really get the crucial differences between primary and secondary uses.

Short blocks, alas, tend to be viewed as insignificant if noticed at all. It’s no surprise that one-offs such as Roy’s Square are forgotten. But multiplied over a city or a metropolitan area, and the absence or loss of short blocks undercuts street life and economic viability. Implications are lasting and hard to correct.

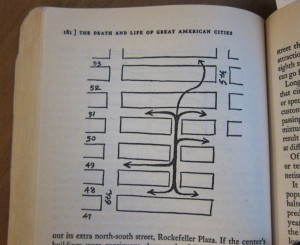

In Chapter 9, “The Need For Small Blocks,” Jacobs combines common sense, basic observation and rudimentary maps of streets in Manhattan’s West 80s, between Central Park and Columbus Avenue, to illustrate how longer blocks isolate pedestrians, limiting their options and leaving many streets “stagnant backwaters.”

“The supply of feasible spots for commerce rises considerably” when street grids increase chances for pedestrians to turn corners. Even slight variations in sidewalk traffic will make or break nascent enterprises, so it’s easy to see how seemingly minor changes to street patterns trigger virtuous and vicious cycles.

The chapter, the book’s shortest at just nine pages, explains a mystery that baffled New Yorkers after street-deadening elevated rail lines were removed from 3rd Avenue and 6th Avenue. On the West Side, where the blocks were long, the move had little effect. On the East, with its short blocks, revitalization erupted.

Of course, cities are complex and organic, so it’s foolish to consider conditions in isolation, something Jacobs reminded me of in a 2005 discussion on block-length effects in Toronto.

Referring to the underperforming Sheppard subway, she decried local media’s fixation with the new residential density along the line. “A few tall buildings don’t constitute healthy urban form. Even near the stations, people aren’t walking in large numbers,” she said, pointing out that land uses remain separated and there aren’t enough primary uses attracting people.

Furthermore, because the area can’t provide a real mix of building ages for generations, she said it’s doubly essential the other diversity generators be present. “As long as the blocks are long, you can be sure the area will be off-putting for pedestrians and, for the most part, economically barren,” she said. “Density in the absence of short blocks is usually trouble.”

Regarding Danforth Avenue east of Pape, Jacobs indicated that those who noticed the area’s decline as car ownership grew and after subway replaced the streetcar in 1966, tend to overestimate transportation’s role. “If this is like typical blue-collar neighbourhoods from the early 20th century, you’ll find there was significant loss of industry after the war,” she said. “These losses devastated the area’s primary-use mix.”

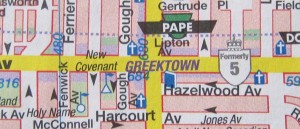

Then, after a warning about how misleading maps can be, she said my quest to understand the Danforth’s split personality should “start with a good, scaled map; compare block lengths.”

Sure enough, the things she identified in New York apply here. To the west of Pape Ave., in Greektown, where businesses and sidewalks thrive, it takes less than a minute to walk most blocks at an easy pace. Sometimes 45 seconds will do.

The first south-side block east of Pape is unbroken all the way to Jones Avenue and takes nearly four minutes to walk. The long-block east-west streets to the south have little real connection the Danforth. And all through the areas further east, often called the “Other Danforth,” where a “blight of dullness” arises, long blocks dominate at least one side of the street until the rail corridor veers close enough to do further damage by truncating neighbourhoods to the south.

From Roy’s Square, to the Danforth, to New York, Europe and beyond, the role of vitality’s four generators is universal. But while we often add density and mixes of uses, and we sometimes let our buildings age, we rarely add streets and shorten blocks.

It troubled Jacobs to the end.

The best way to thank her for explaining this crucial detail, which was hidden in plain view all along, is to ensure we leave as many small blocks as possible to our descendants.