Urbanist Jane Jacobs may never have written about the East Danforth, but after a few long walks on a Toronto strip that was in decline for much of the latter 20th century, she developed firm views on what is needed for revitalization.

By STEPHEN WICKENS

When the writing wasn’t going smoothly, Jane Jacobs would take a long walk. During one stretch of gorgeous fall weather in the early 1980s, with writer’s block delaying progress on Cities and The Wealth of Nations, the renowned author of books on urbanism, economics and ethics visited the Danforth “three or four times … the whole strip from Broadview to Victoria Park,” with several detours to the nearby rail corridor and the surrounding streets.

She never wrote about those Danforth jaunts but she spoke with me about the area in 2004 and 2005, while I was both writing Toronto features for The Globe and Mail, and working with people attempting to start a neighbourhood group (prior to the eventual and successful establishment of the Danforth East Community Association).

Though she was nearly 90, Jacobs’s memory was excellent. I was raised in the east end and live in the immediate area. I walk a lot, too. She visited a few times – decades earlier – yet what she said helped open my eyes.

In one discussion, she bristled and became animated when I mentioned the usual received wisdom, that the East Danforth’s seemingly mysterious decline in the second half of the 20th century was likely a result of transportation changes, most notably the replacement of streetcar service with the Bloor-Danforth subway in 1966 to Woodbine, and 1968 farther east. It is an enduring theory, given legs within weeks of the subway’s opening as media latched onto attempts by the area’s “business men’s association” and locals to restore some form of street-based local transit, either streetcars or buses, that would run parallel to the subway using existing, frequently spaced stops. The group produced a 15,000-signature petition (huge numbers for a small area in the pre-social media days), but the pleas were ignored at the Toronto Transit Commission.

Jacobs said far too much weight had been given to the arrival of the subway, and called it a ‘lazy man’s theory.’ She agreed that underground subway stations – spaced much farther apart than the old streetcar stops – sped the processes that were sucking life off the street (better planning for second station entrances could have helped a bit, in her view). But she argued that commercial strips of blue-collar neighbourhoods had gone into similar declines during the same era, “all over Toronto, the continent, even the planet – and almost none of these other strips would have had new subways.”

Commercial streets, an essential component of urbanism for millennia, had, in effect, been deemed obsolete in theory and practice, and the ramifications were both far-reaching and subtle.

The larger transportation-related factors in her view were that car ownership was soaring in the post-World War II era, and that people were suddenly traveling farther to shop – to malls and bigger stores where parking was easier. People also became increasingly less likely to leave home on foot, and whole neighbourhoods and cities suffered as a result.

“Transportation matters to the discussion, to be sure,” she said. “But if you’re serious about revitalizing this street, you’ll focus on broader changes to the overall local economy, and you’ll look for adjustments to form that will naturally attract pedestrians for day-in day-out reasons.”

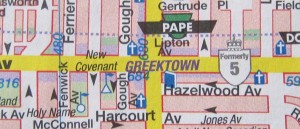

Among the things that first struck Jacobs on her walks, especially east of Pape where the nature of the street changes suddenly, was the near complete lack of Victorian or Edwardian buildings. She also found a sudden increase in the lengths of the blocks (see No. 2 in her seminal list of conditions for generating diversity).

——————————————————————————————————–

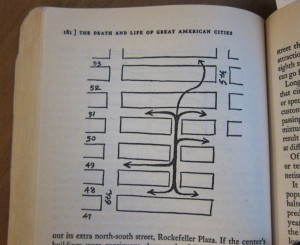

Jane Jacobs’s four conditions to generate diversity and vibrant city streets, from the The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Page 150:

- The district, and indeed as many of its internal parts as possible, must serve more than one primary function; preferably more than two. These must insure the presence of people who go outdoors on different schedules and are in the place for different purposes, but who are able to use many facilities in common.

- Most blocks must be short; that is, streets and opportunities to turn corners must be frequent.

- The district must mingle buildings that vary in age and condition, including a good proportion of old ones so that they vary in the economic yield they must produce. This mingling must be fairly close-grained.

- There must be a sufficiently dense concentration of people, for whatever purposes they may be there. This includes dense concentration in the case of people who are there because of residence.

——————————————————————————————————-

She advised me to compare the block lengths east and west of Pape on a map. “Better still, walk and time them if you have the opportunity,” she said.

It turns out that most blocks on both the north and south sides of Danforth west of Pape, the much livelier Greektown neighbourhood, are no more than 100 metres and can be walked in a minute or less. Many to the east take two minutes or more. When we touched on this in a subsequent discussion she said I’d probably remember for the rest of my life that blocks in the liveliest places in cities all over the world will tend to be well under two minutes in length at my pace (see for yourself, no matter where you live or where you’re visiting). “Two-hundred and fifty or 300 feet is ideal in most cases.” (That’s 76 to 91 metres.)

But Condition No. 1 on her list, The East Danforth’s mix of primary uses, would in her view matter most to people puzzling over how to reinvigorate the area (the emphasis on the word primary was hers). She felt strongly that if redevelopments merely added residential condos with retail on the ground floor, we wouldn’t be adding the type of mixed use that could have a major regenerative effect. We might merely be adding to the number of empty stores, she said. And she warned that many “seemingly enlightened planners still tend to have a superficial understanding of what mixed primary use really means.”

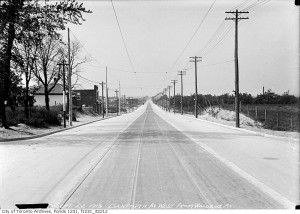

Jacobs suggested I go to the Central Reference Library and use city directories and old maps as an introduction to the timeline of Danforth East’s development. Correctly, as it turned out, she told me to expect that the area was first developed largely in the 1920s, a point she said meant this was in fact a hybrid, not the pure streetcar suburb that some academics would label it. Private cars would have been a factor from the beginning, certainly east of Pape, even if the area had still developed largely around a main street on which streetcars arrived in 1915. She told me to look for evidence the area developed with a significant amount of employment, mostly industrial and most of it likely focused on the rail corridor to the south.

And it was there.

Prior to the area’s initial development, but well into the 20th century, lands on both sides of the East Danforth were largely operating as market gardens, providing fresh produce to the nearby city. Farming operations got larger farther north, toward the Taylor Creek valley, with several dairy operations in what was the Township of (and later the Borough of) East York, amalgamated into Toronto in 1998. Most of the area immediately north of Danforth had been Church of England reserves, known as the Glebe and usually leased to farmers. South of the Danforth (east of Greenwood and over to the town of East Toronto at Main Street), was known as Upper Midway, part of the Midway area annexed to the city in 1909. It was very rural compared with the main parts of Midway, south of the tracks, and it appeared as a virtual blank on maps as late as 1907.

Jacobs asked me to come up with a plausible explanation for the delay in development until after World War I, especially since areas farther from established Toronto had developed sooner (around the Grand Trunk/Canadian National station and yards at Main Street). I’m open to arguments, but it seems probable that the biggest delaying factor was that, east of Pape, five creeks crossed the Danforth (a.k.a. The Second Concession and later The King’s Highway No. 5). The railway tracks had also established themselves as a barrier. Though the tracks had brought the Town of East Toronto to life, the corridor barrier itself would increasingly become a drag on the area in the later 20th century, especially as it got closer to the Danforth heading east and as industry that once provided jobs in the area moved out to the suburbs.

Though the Danforth (originally the Don and Danforth Plank Road) had opened in 1851, the imposition of a concession grid, forced the street to follow a predetermined straight line, despite ravines and marshy areas that would not have been apparent in the kingdom’s Colonial Office in the 1790s. The road’s path was set decades before surveyors arrived. The Danforth was a nightmare to maintain (a job left largely to the farmers who used it and paid tolls — a source of protests and legal disputes). The rickety wooden bridges often got washed out. And even when they weren’t, travelers to the city still had to get to down to Queen, Gerrard or Winchester streets to cross the Don Valley.

Even though streetcar service and proper paving came to the East Danforth in 1915, development didn’t happen until a housing shortage after the Great War and the opening of the Prince Edward Viaduct in 1919. Something that also held up residential development in the immediate Coxwell-Danforth area was a stench from the Harris abattoir and rendering plant, which was eventually driven away in the early 1920s (and though this is also a clear instance where employment and residential don’t work in close proximity, even the Harris plant attracted a small enclave of residents using kit housing just southwest of Danforth and Coxwell).

In the city directories, Jacobs suggested I look for trends related to the stores that sprang up: Aside from the fact that many merchants lived upstairs from their businesses, the most stunning thing was the lack of turnover. Vacancies were listed when buildings were new in the 1920s, but were almost non-existent again until the late 1950s. There was very little turnover among businesses through the Great Depression, 1940s and early ’50s, indicating a healthy local business environment despite great challenges facing the global macro-economies. Even when Woolworth moved from east of Woodbine to snuggle up next to department store rival Kresge in 1942, displaced shops found ways to stick around — some at Woolworth’s old site.

The variety of shops, especially close to Woodbine was remarkable. Though supermarkets in the 1950s were much smaller with limited offerings, there were nine of the Loblaws, A&P and Dominion variety from Greenwood to just east of Woodbine), as well as butchers, bakers and produce shops. There were also many clothing and shoe stores, and the three movie theatres would have contributed to sidewalk life in the evenings.

These were all things Jacobs expected me to find, and she said it was important to note that the turnover and vacancies started appearing well before any subway construction began, even if locals didn’t really pay attention to the strip’s decline till later. Some feared the subway would bring over-development, yet the opposite happened, and many are still astonished by the lack of development more than 50 years after the subway opened.

There is also a strong likelihood that plans for an extension of the Gardiner Expressway into Scarborough, through the neighbourhoods straddling the railway tracks, hung over the local real estate market in the 1960s and ’70s. Hundreds of homes were to be expropriated just for the interchange at Woodbine, not far south of the Danforth.

As for industry and employment, there wasn’t so much right on the Danforth itself, though it’s worth noting that Canada Bread had its main Toronto plant just east of Greenwood (and the folks at the Linsmore Tavern said the plant workers kept them very busy on breaks and shift changes). Ford of Canada, before moving to Oakville in the 1950s, had its main operations at what, in 1962, became the Shopper’s World Mall, west of Victoria Park, right by the eastern loop of the streetcar line on a small strip where East York actually reached down to the Danforth.

Jacobs called the loss of that employment and the fact that some Danforth stores moved to the mall in the early 1960s a “double whammy” for the strip. Car dealerships and the TTC streetcar barns at Coxwell (now only partly used, and mostly as parking for subway staff) also brought lots of workers to the neighbourhood or provided jobs that local residents could walk to. And, of course, lots of people working in the area provided essential daily business for local shops and restaurants. Along the rail corridor, less than a half-kilometre to the south, were major industrial enterprises, including a John Wood plant on Hanson Street, the largest source of hot water tanks in Canada from the 1920s on. Service Station Supply was an assembly plant for gas pumps and hydraulic lifts. There was a factory producing stoves, washers, ‘ice boxes’ and fridges. There were many light industrial operations as well as quarries and brickyards on either side of Greenwood. Major suppliers of coal, lumber and other building materials were located all along the tracks from Greenwood to east of Main, where the CNR shops and freight yards began.

Jacobs wanted me to see that, while many preferred to drive out from of our neighbourhood the noise and trucks that increasingly accompanied industry, the shift to an overwhelmingly residential area quietly undercut essential facets of the local economy, including the shops and restaurants on the Danforth. The loss of industry meant the rail corridor bordering the southern parts of the neighbourhood shifted from attracting much economic activity to the East Danforth to being a barrier and a drag on the area, a hindrance to walkability and connectivity.

Late in the 20th century, even though household sizes got smaller, in pure residential terms the neighbourhood actually got denser because housing was built on former industrial land. But the mix of primary uses – usually residential and employment, with a few specialty shops or large theatres that can draw people from other parts of town – was getting badly depleted.

Looking forward, she said: “Residential density itself won’t be enough of an answer if you really want to create or recreate a vibrant neighbourhood,” she said, adding that residential density by itself, especially if it becomes high-rise, high-density could be a big problem if we don’t pay attention to all the generators of diversity.

On that count, she said the options are limited. There might be small gains to be had by breaking up some long blocks, but the new passageways or streets would almost certainly never penetrate more than a block or two into the surrounding neighbourhoods. Creating a deep inventory of buildings of different ages is a long-term organic process; the key would be to ensure that the 1915 TTC barns and much of the 1920s buildings be saved (likely not a problem with the fragmented ownership and often shallow lots). Density increases, especially right on the Danforth would be helpful, but we might need less than many think, especially if significant employment is included.

“There’s opportunity in bringing employment to sites at the subway stations,” she said (and she agreed that the TTC lands and some north-side parking at Coxwell and the Valumart parking lot at Woodbine are probably our only significant options for bringing mid-rise office buildings into the local mix. (Our discussion didn’t consider areas as far east as Main Square and Shopper’s World, but clearly, there’s redevelpment potential there).

She added that we were lucky to be approaching things at this time (she was speaking in 2004) because much of the GTA’s employment gains are likely to be in office work, and that even just a few mid-rise office buildings near the stations might bring enough workers to help “rebalance the local economy.”

Though she died in early 2006, Jacobs lived long enough to see a resurgence of life downtown when usage restrictions were lifted on “The Kings,” and when a new wave of residential development was able to complement the dense employment zones, allowing secondary-use shops and services to come back in the core. She saw it as encouraging.

Returning employment to the Danforth area could, in her view, have a similar effect (though on a much smaller scale) by getting more people out onto the sidewalks for different reasons at different times of the day, helping lots of small shops and restaurants to “get over the hump … it often takes just a handful of extra customers a day to make a difference in small-scale retail.”

She emphasized that year-round walkability relies heavily on people having regular economic reasons to be out on the local sidewalks. “You won’t get industry again, and few would tolerate it, but office work and some new residential density right on the Danforth could be great for the city and your area.” She felt the Avenues focus in the city’s Official Plan could be life-giving for the East Danforth.

She also noted that the Danforth has spare subway capacity in what transportation people call the ‘contra-flow,’ – half-full trains going in the opposite direction of the main rush-hour crowds. She called that “untapped potential.” She remembered surface parking near some of the subway stations and called that “a waste of potential.”

“This may come as a surprise to you,” she said, “but part of the area’s empty-store problem is that there’s too much retail space for the current size and makeup of the local economy. Most of that retail is going to be secondary-use stuff.”

Demand for the retail space on a strip such as the Danforth, in her view, was very much a reflection of the health and diversity (or lack thereof) in the wider local economy. It’s almost certain that she would have been a huge supporter of DECA’s pop-up shop program. She said: “Vacant storefronts certainly feed vicious cycles of decline, but if you’re smart, long-term, you’ll view them (and street crime) as mere symptoms of bigger problems.”

Anyway, it’s a gorgeous September day and signs of new life have been popping up on the East Danforth for nearly a decade now. Even though the writer’s block isn’t necessarily holding me back, I think I’ll go for a walk.

————————————————————————————————-

Stephen Wickens is a journalist and a former board member of Danforth East Community Association. At present he leads DECA’s Visioning committee. Much of the material gathered from talks with Jane Jacobs (directly and indirectly) forms the basis of an annual Jane’s Walk, ‘The Death and Life of Upper Midway.’