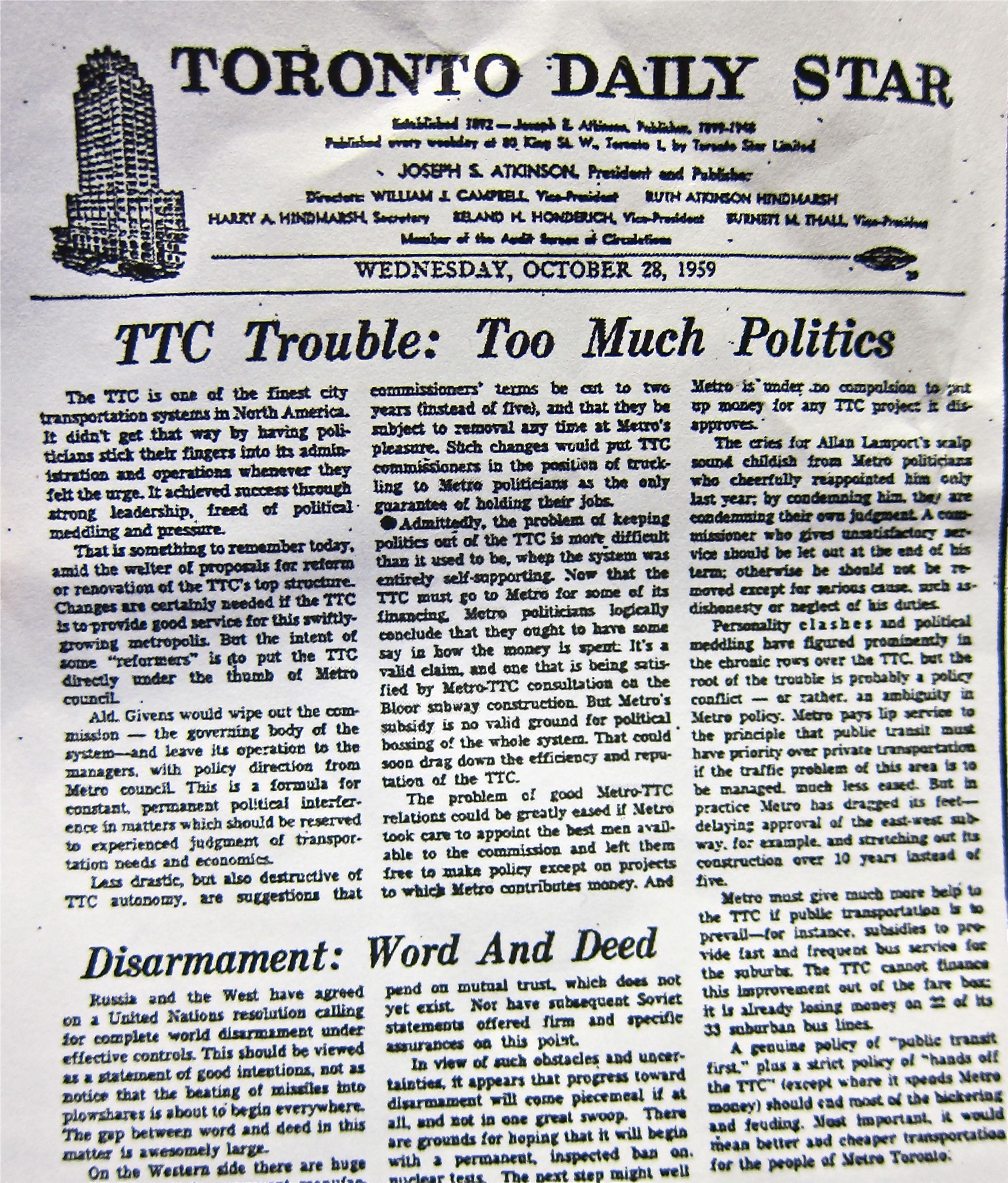

The following post illustrates potential flaws in the SmartTrack and Regional Express Rail planning and assessment process by looking at the case of an almost certainly vital station site that appears to have been overlooked altogether. This note was prepared as feedback for the public consultation process and was submitted in August 2018. Today, Sept. 25, 2018, I received by email a form letter from the office of Environment Minister Rod Phillips dated Sept. 19, basically saying my concerns are frivolous. Judge for yourself. Anybody interested in seeing the PDF files of the 2014 TTC report, the Ministry’s “Confidential” SuperGO report from the 1970s or the Environment Minister’s letter should contact me by email at stephen.j.wickens@gmail.com.

I’ve held off posting this until now to give the province an opportunity to reply. The main point is that our process for evaluating and planning transit infrastructure is broken and that this should be a major concern for all levels of government, especially a new government that has promised to change things. The decision not to seriously tackle our transportation problems has had, and will continue have, a massively negative effect on Ontario and the Toronto area’s competitiveness and livability, while undermining the confidence of people in our democratic processes.

August 20, 2018

Feedback including objections regarding negative impacts of the current station plan for SmartTrack:

Submitted to:

– Jade Hoskins Senior Public Consultation Co-ordinator, City of Toronto (SmartTrack@toronto.ca)

– Georgina Collymore, Senior Adviser, Communications and Stakeholder Relations at Metrolinx (newstations@metrolinx.com)

– Cindy Batista (Special Project Officer, Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks (Environmental Assessment and Permissions Branch) (cindy.batista@ontario.ca)

From Stephen Wickens, East-end Toronto resident and semi-retired journalist with a lifelong interest in transportation and commercial real estate matters. (stephen.j.wickens@gmail.com)

A little background: As I’ve written on a few occasions (in newspaper columns, in email and face-to-face discussions with private- and public-sector transportation professionals and on social media), there is the germ of a very good idea in the SmartTrack (ST) plan and much opportunity in how it can piggyback onto Metrolinx’s Regional Express Rail (RER) initiative. But for reasons that appear to include political intransigence and interference at inappropriate places in the planning process, as well as an inability to think long term and an unwillingness to seriously consider international best practices, both plans appear set to fall considerably short of their potential in terms of service provision and value for the public’s investment dollar, as well as in serving established provincial policies on the social-equity, environmental and regional-planning fronts.

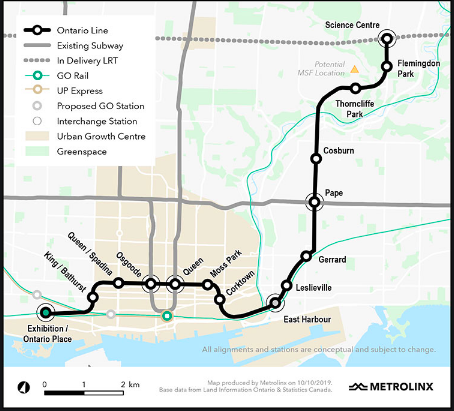

I’ll confine today’s comments primarily to how the process so far has somehow eliminated – apparently without any serious or documented study – a station that is clearly among the most necessary if SmartTrack is to seriously attract new transit users and provide at least some short- to mid-term relief to the overcrowded parts of Toronto’s subway system. But to make the case properly, I’ll have to stray a little and I hope you’ll bear with me.

Two more points before getting to the meat of the matter:

- While I don’t have formal education on public transportation matters, public transit locally and internationally is a file I’ve followed closely since the 1960s. For decades, some of the most respected transportation professionals in these parts have generously kept me in their loops, sometimes even seeking my opinions or help in answering questions.

- Among the most important things I learned when writing about transportation for Toronto newspapers is that unnamed sources are essential to getting at the truth because bureaucrats and private-sector professionals alike are often uncomfortable speaking truth to power or candidly on-the-record with journalists, at least until they’re retired https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/toronto/what-went-wrong-since-the-golden-age-of-toronto-transit/article34321708/. For this note, I’ve tried through official “communications” channels to obtain relevant information that was lacking in the public realm, but I was forced again to have several off-the-record discussions with past and present Metrolinx employees, city staffers, Toronto Transit Commission staff and people working for consulting and engineering firms the city and province use. Because I can’t reveal identities of some who’ve helped me, I’ve decided not to use names of anyone (though some identities may be revealed upon request). This is not about people or embarrassing anyone, it’s about getting good results in this specific case and, possibly, improving processes so we can start getting better transit decision-making over all in future. Without that, Toronto and Ontario will continue at a serious competitive disadvantage in an increasingly globalized world.

Mind the gaps

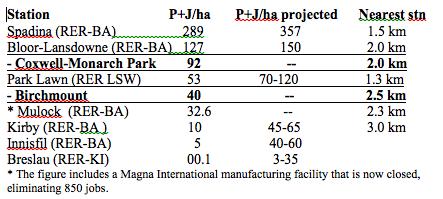

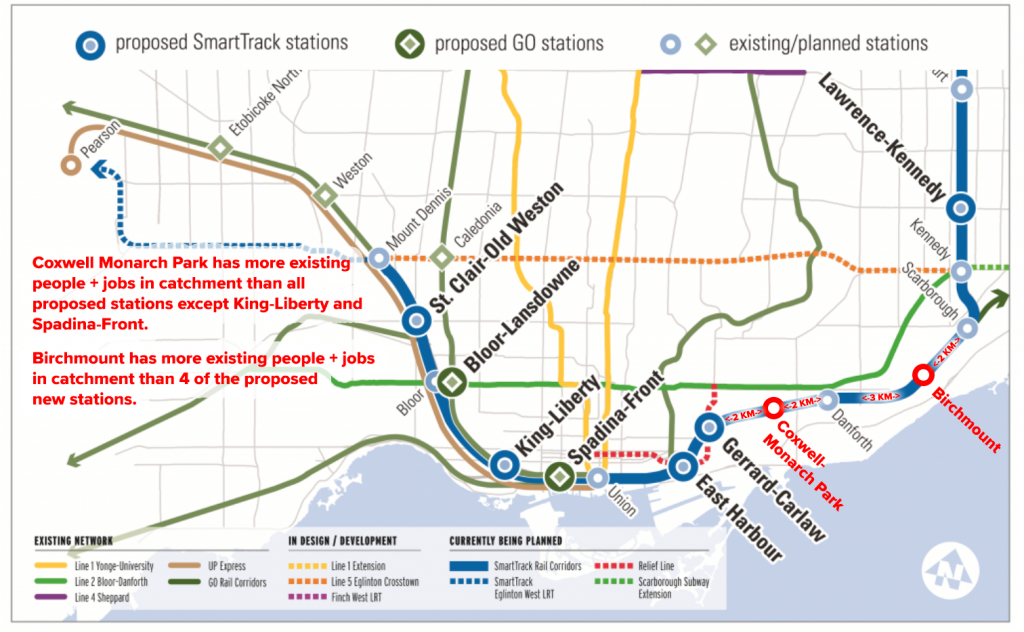

The primary selling point of the SmartTrack plan is that frequent, somewhat subway-like service on an existing above-ground corridor at a TTC fare could deliver some relief to the overloaded core of Toronto’s subway system far sooner than the proposed never-today/always-tomorrow Relief Line subway. Yet, for reasons that seem not to exist in any available documentation, the area of the proposed SmartTrack route with the greatest potential to deliver that relief to the subway is being left with the longest gaps between stations.

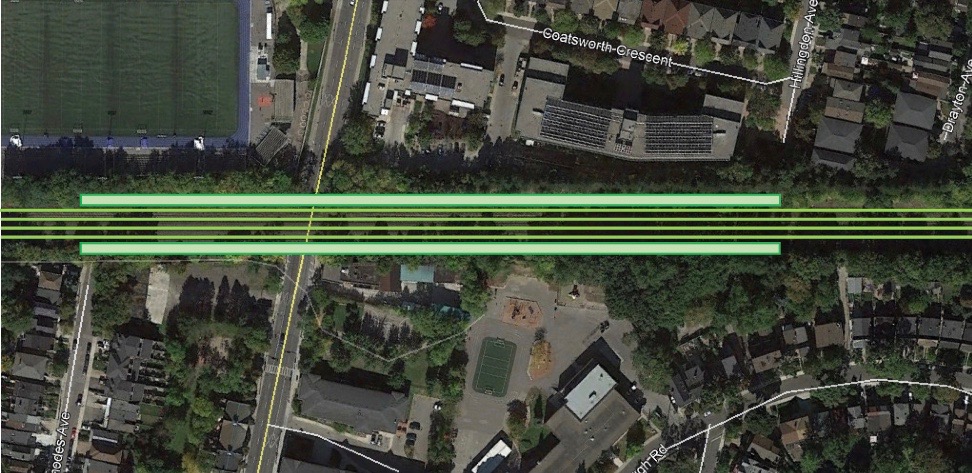

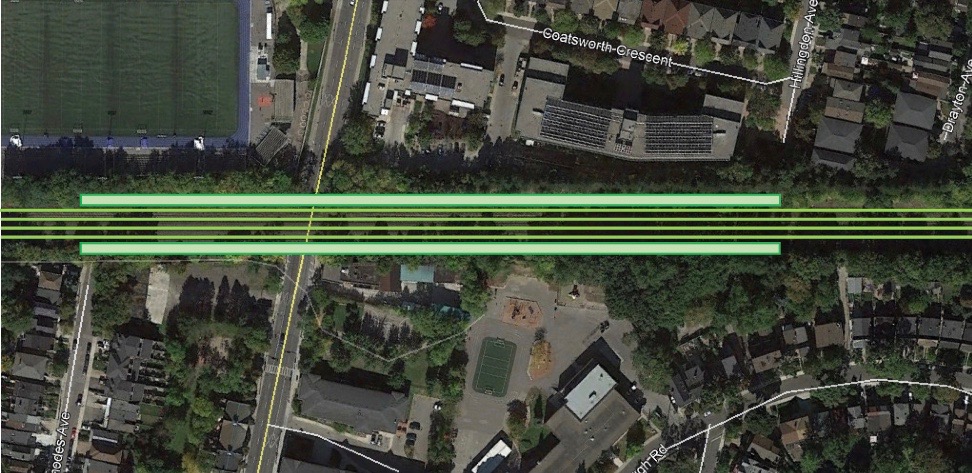

While much of the ST route calls for two-kilometre station spacing, it’s a full four kilometres from the proposed station at Gerrard Square (where SmartTrack might eventually connect with the proposed Relief Line) to the next station east, GO Danforth. (And the next station heading east from GO Danforth is another five kilometres.) The subject came up over dinner with transit-planner friends a couple of years ago and it was agreed that Coxwell Avenue, roughly 2 km from both GO Danforth and the proposed Gerrard-Square station, seems to be an ideal location for addressing this void. Little did we realize that upon looking at the situation more closely we would discover the case for a Coxwell-Monarch Park SmartTrack stop was much stronger than the cases for nearly all approved ST and RER stations.

Can something as big as a railway station fall through the cracks?

A few months after that dinner, in August 2016, Metrolinx contacted the Danforth East Community Association about setting up a meeting with community members regarding plans for upgrades to the GO corridor (which is the southern boundary of DECA’s area). The meeting with DECA’s visioning committee (which I co-chair) took place on Sept. 13, 2016, in the basement of Gerrard Pizza (near Danforth and Coxwell). As expected, area residents raised concerns about noise associated with increased train frequency. And some wanted to know why we were already having to add a fourth track when “it seems like only yesterday” that GO was keeping them up all night with construction to add a third track (it was actually about a decade ago). One woman added: “Why couldn’t they get it right the first time?” (As we’ll see toward the end of this note, there are also valid reasons to question Metrolinx’s commitment to getting this bit of the Lakeshore East corridor upgrades right the second time.)

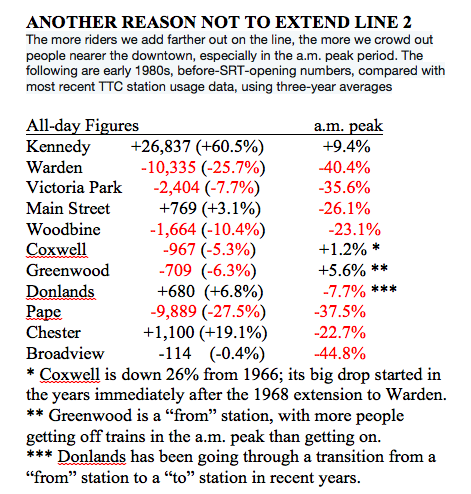

Some meeting attendees, sick of crowding and unreliable service on the TTC, also had some “what’s in it for us?” questions. Possibly seeing an opportunity to deliver good news, the man leading the three-person Metrolinx entourage, eagerly mentioned the proposed Gerrard Square station. He and the other Metrolinx staffers appeared quite surprised when it was pointed out that a station at Gerrard Square – like the TTC’s Relief Line proposal – would be too far west to do much for people who already can’t rely on being able to squeeze into jammed subway trains at Woodbine, Coxwell, Greenwood and Donlands in the a.m. rush.

When asked about the possibility of an SmartTrack station at Coxwell, the lead Metrolinx representative replied that he was certain the site had been studied using “strict criteria” and that the idea must have been rejected by experts.

I then asked him to provide me with the reports from that study process, particularly with regard to Coxwell-Monarch Park or a station in the long no-man’s land between Gerrard Square and GO Danforth. He said he would be happy to send me the details and that I should email him a reminder. Thus began a long back and forth for which Metrolinx – nearly two years later – remains unable or unwilling to provide any such documentation, detailed or otherwise.

What Metrolinx was able to tell us

Anyone who has studied Metrolinx’s many official online reports regarding RER, SmartTrack and the station-selection processes will have read repeatedly that “An initial identification of over 120 potential station sites was narrowed to 56 (it says 50 in some reports) with supportive infrastructure through a high-level evaluation of transport connectivity, planning and land use and technical feasibility.” Coxwell was listed as a potential station on an initial Metrolinx compilation of 120 potential stops. Coxwell was also under consideration after the list had been winnowed to 50 (or 56, depending the document). At some point after that, but before the initial business case studies began, Coxwell disappears from the list. That’s about the extent of it … unless you consider what I was told by one former Metrolinx staffer (who had yet to leave when the cut-down process and/or any early-stage studies would have taken place), including:

- “I asked the same question of MX Planning [about criteria and results used for eliminating stations early on], as they engaged us in Economic Analysis shortly before they started Stage 6 (the business cases) for the short list. They didn’t do any modelling for the lists of 120 or 50 stations, the decision was subjective … ”

- “Remember what [X. XXX] said to me during my exit interview: ‘Let’s face it, everyone fabricates the evidence: the city does it, we do it. The new-stations process was always going to be political.’ ”

The former staffer, as well as two current ones, also mentioned in recent years that even when Metrolinx got around to modelling business cases for the short list, some key criteria that were used were chosen with suburban commuter rail in mind and was thoroughly inappropriate for the urban areas to be served by SmartTrack. They’ve also pointed out that at least one of the technical feasibility rules regarding stations on curves was broken for stations that politicians in positions of power were demanding.

Meanwhile, two senior bureaucrats, one with the city and one formerly with the TTC, have told me that the only stations considered for SmartTrack and for study by Metrolinx were chosen – not through a rigorous professional process – but by advisers to the winning campaign in Toronto’s 2014 mayoral race. And while the current mayor’s office eventually gave in on an obvious flaw in the initial ST plan (the since-killed western spur along Eglinton), it seems apparent that no serious second thought was ever given to addressing potential flaws or better solutions in the SmartTrack plan for the old city’s east end and Scarborough.

The broad east-end transit context

My discussions in recent years with city staff regarding several issues (including the Danforth Avenue Planning Study, the Main Street Planning Study, two individual high-rise development plans for Main and Danforth, Metrolinx’s RER-ST corridor upgrades and SmartTrack itself) have often indicated that the official view from City Hall is that the east end of the old city is very well served by transit, and that a relief subway (aimed primarily at dealing with dangerous and off-putting crowding on the Yonge subway and at Bloor-Yonge station) would solve any possible east-end concerns – even if the line comes only as far east as Pape.

And that received wisdom might seem valid if you don’t look much beyond simple maps. But a close look at long-term transit-usage trends in Planning District 6 (the four pre-2018 city wards abutting the Bloor-Danforth subway between Victoria Park and Broadview) indicates otherwise. Most of the key details on this point can be found in these two 2016 columns I wrote for the Beach Metro News:

(Though newer Transportation Tomorrow Survey data have been released since these columns were written, sources tell me there’s a strong chance the data are suspect. With only a 7-per-cent response rate, I’m hesitant to put stock in the new TTS numbers until a trusted transit data analyst I’ve worked with previously has a chance to seriously study them).

Five key points for understanding the east-end context include:

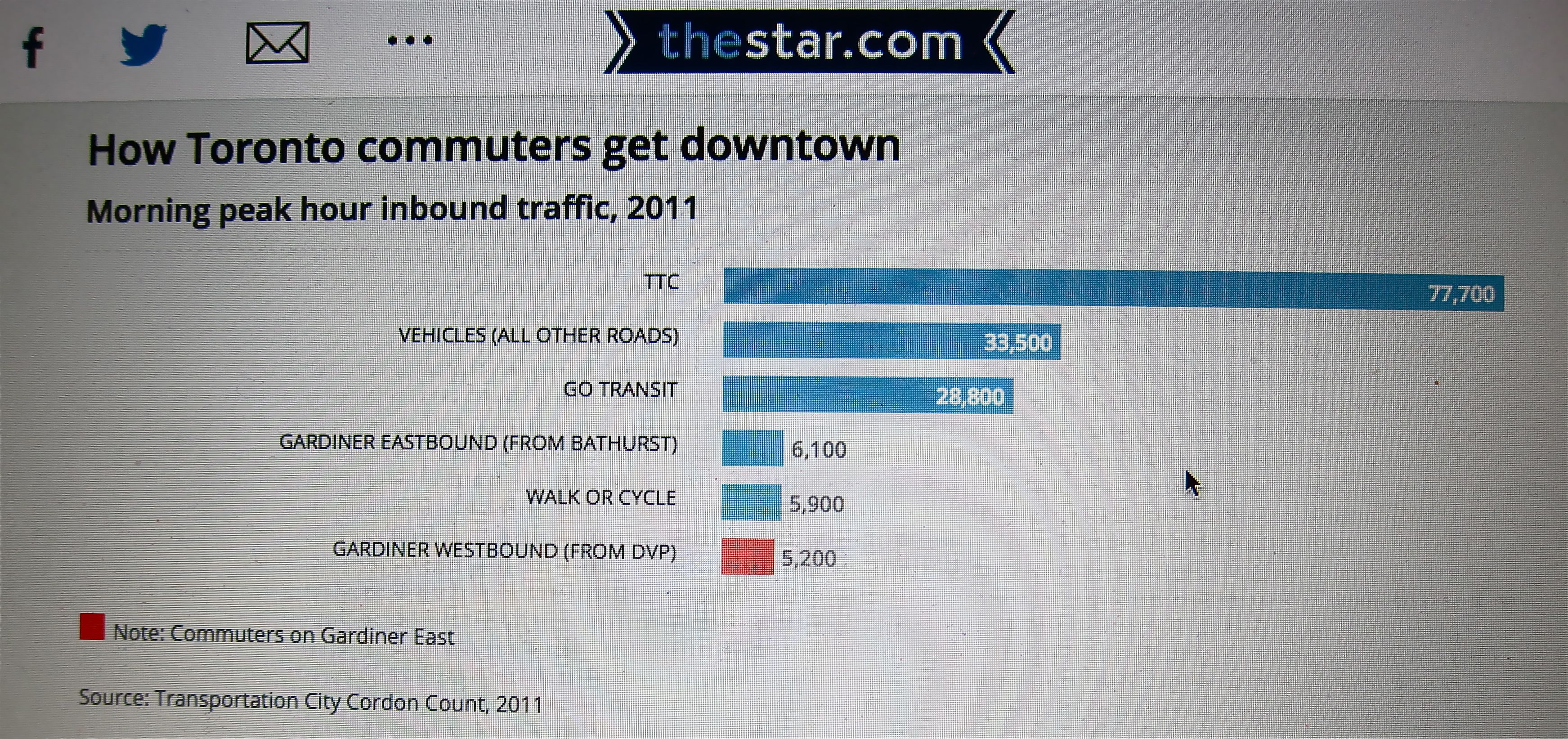

- PD6, despite being an inner-ring planning district that should be easy to serve by relatively low-cost transit for trips to the nearby downtown, has seen transit lose so much market share for such trips that, as of 2011, it had the lowest percentage of transit use for downtown a.m. peak trips of any Toronto/416 planning district (yes, that includes Scarborough, Etobicoke and North York). And, all the while, car usage was on the rise for downtown trips from PD6.

- PD6 is the second biggest generator of trips to the core of any GTHA planning district – it’s a market that really matters, with major potential for ridership gains without huge investments;

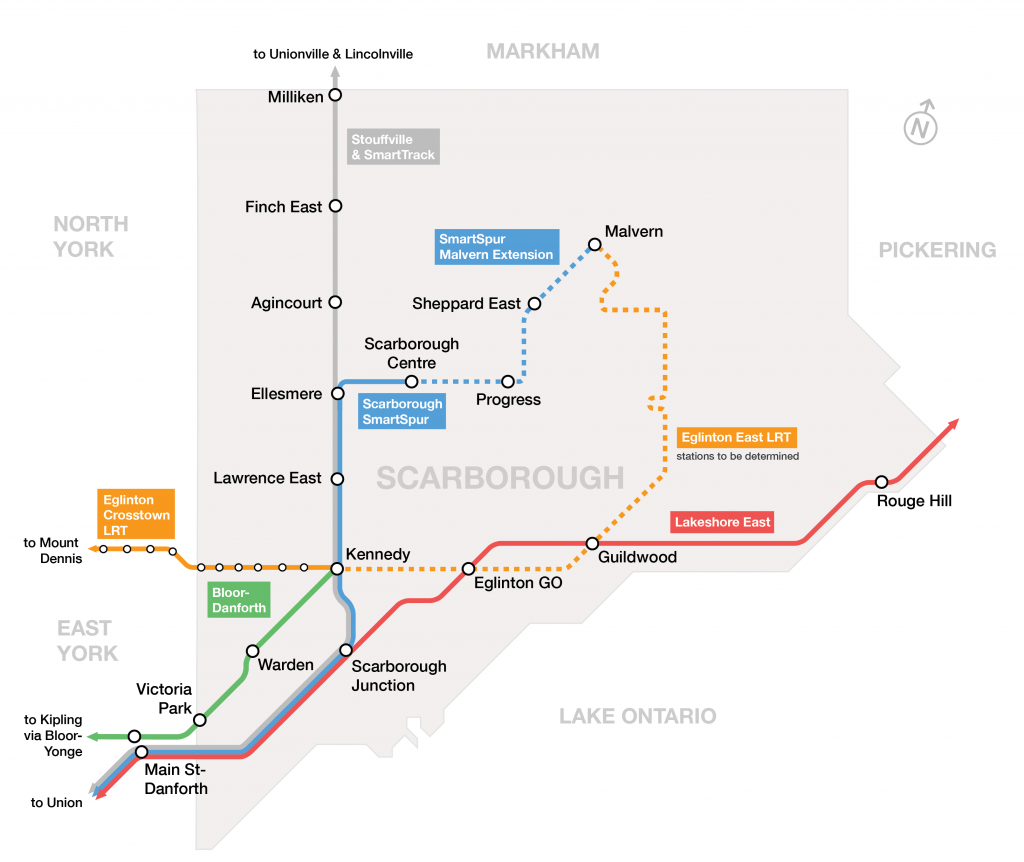

- Since the Scarborough Rapid Transit (SRT) line opened to Scarborough Town Centre in 1985, Bloor-Danforth subway trains have filled up east of PD6, while crowding at the Bloor-Yonge pinch-point becomes increasingly dangerous. If the proposed multibillion-dollar Scarborough Subway Extension succeeds in attracting more riders to Line 2, the problem will only get worse. A 2014 TTC report shows the seven stations from Warden to Donlands, inclusive, have been losing ridership in the a.m. peak over the past 30 years, likely due to crowding that won’t be solved even if the Relief Line is ever built.

- Areas east of the Don River have only two trunk east-west TTC lines between the lake and Danforth Avenue, unlike the areas further west, which have five, including major TTC routes on King, Dundas and Wellesley-Harbord (I’d add Queens Quay, but that’s not fair). Furthermore, the two lines that penetrate the east end, the Queen 501 and the 506 Carlton (which largely runs on Gerrard in the east end), have seen service cuts over the past three decades that have resulted in big ridership losses (without helping helping the TTC balance sheet). Because it’s bordered by the Don Valley on the west and north, PD6’s road connections to the rest of the city are also limited.

- GO trains roll through the east end (largely empty outside of the rush hours) without stopping in enough convenient places, while charging uncompetitive transit fares. For many east enders, GO trains serve only to disrupt sleep or force conversation breaks when they roar past.

The narrow Coxwell-Monarch Park context

For me, a brisk walker, it’s 25 minutes on foot from the bridge that carries GO trains across Coxwell Avenue to GO Danforth and the proposed SmartTrack station at Gerrard Square. Taking the TTC to those stations isn’t much faster, at least if my small sampling counts for anything. My five weekday trips to or from GO Danforth took 19.5 minutes on average; three test trips to Gerrard and Carlaw averaged 20 minutes and 16 seconds – and, of course, once at those stations another separate fare would be required to travel farther. (Two of the four trips to GO Danforth included nine-minute walks to the Coxwell subway platform because the No. 22 bus was unable to pick me up before I got to the subway).

Despite talk of SmartTrack offering some relief, station location choices made by the Toronto mayor’s office seemed overly focused from the start on proximity to large development sites and not focused enough on pent-up demand (it was also weird that the initial ST plan would ignore existing need/low-hanging fruit in the mayor’s own city while putting terminal stations in Markham and Mississauga). Some of the errant focus appears to have been spurred by misguided advice that tax-increment financing would be a significant source of revenue for the SmartTrack project. And while politically connected developers aren’t likely to enrich themselves spectacularly in the Coxwell-Monarch Park catchment zone, ingredients essential to the any station’s success (criteria that were to be key in Metrolinx’s short-list screening process) are readily available, including the promise of growth and modest but near-guaranteed development.

Five reasons why Coxwell-Monarch Park is a great ST station location

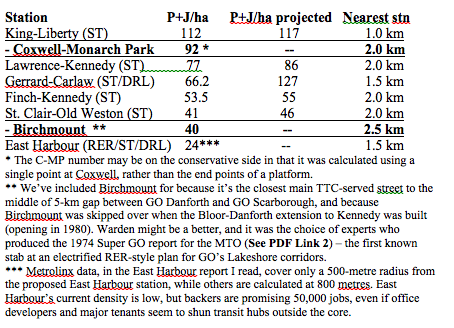

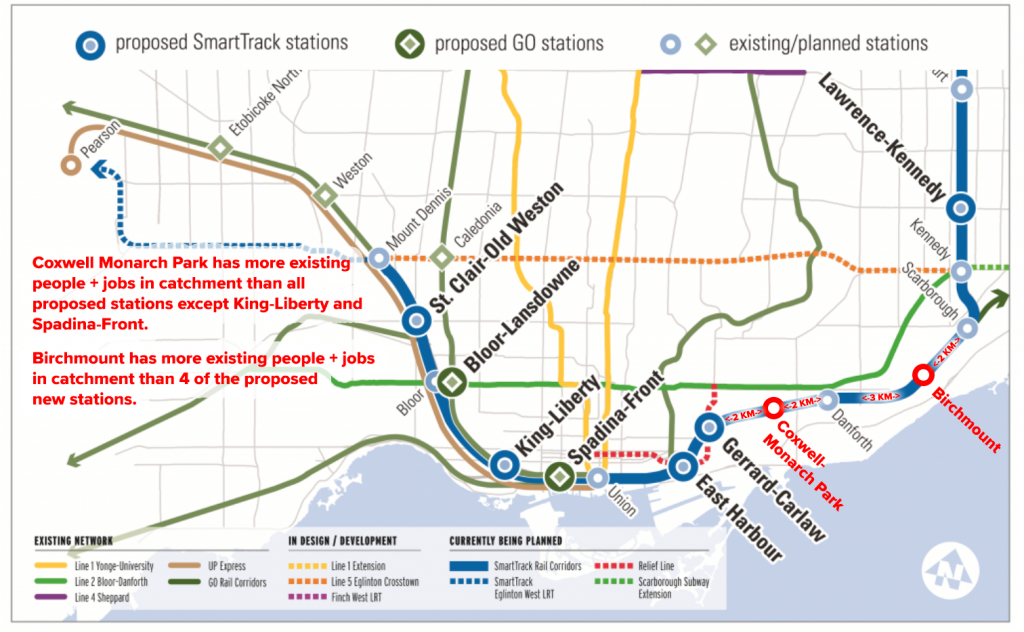

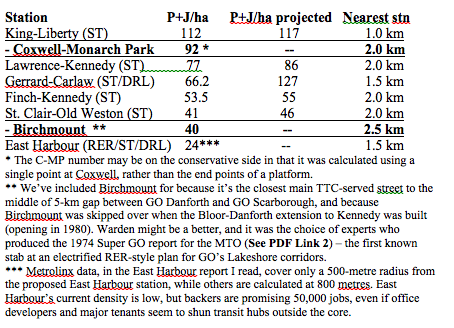

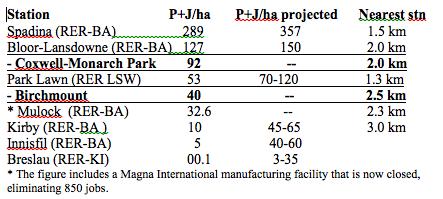

- The Coxwell-Monarch Park catchment zone provides real, existing people-and-jobs-per-hectare numbers that are better than five of the six new stations chosen for SmartTrack, with more growth in the works.

C-MP also fared well when compared with stations Metrolinx and/or politicians at Queen’s Park selected for RER.

The Coxwell-Monarch Park catchment zone’s

- 16,385 residents total is more than in 37 of Metrolinx’s 51 mobility hubs;

- 2,132 jobs are more than in nine of the 51 mobility hubs;

- 18,517 residents and jobs combined, is 85% more than Metrolinx’s 2031 goal for a Gateway mobility hub.

- The Coxwell-Monarch Park catchment zone provides development and growth potential. While no “P+H/ha projected” figure is provided for C-MP in the tables above, there is increasing mid-rise development pressures along Danforth Avenue, which prompted the recently completed Danforth Avenues Planning Study. A mid-rise co-op development is already in the works for Coxwell and Upper Gerrard. Also, plans for a second significant employment node on Coxwell Avenue, led by CreateTO, are in the works for the nearly five-acre TTC site at Danforth, including TTC offices, a mega-police station and community amenities. (The first Coxwell node is slightly north of the C-MP catchment zone, and includes 5,000-plus jobs between Michael Garron Hospital and the Toronto-East York Civic Centre). On both sides of Coxwell, directly south of where the station would be, there are two underutilized half-acre sites, depots for U-Haul and a building-materials retailer (and we’re told Ottawa is looking at ways to make it easier to develop such sites adjacent to railway tracks at stations on passenger-only rail lines). We should also add that large numbers of visitors to and from the sports dome and high school immediately northwest of the C-MP station site have caused enough traffic and parking headaches that a study was commissioned (even though it glossed over the need for transit improvements). The study, by WSP in July 2017, is here: http://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/ward15/docs/1610692701REPMonachPark09062017v12rsrs.pdf

- A Coxwell-Monarch Park station would address social equity concerns. There’s a significant amount of nearby assisted-living projects, including – right next to where the station would go – Toronto Community Housing buildings and seniors homes on Coatsworth Crescent and Amik Plaza’s residences for Indigenous Canadians. (Amik Plaza is operated by Wigwamen, which has other residences in the C-MP catchment zone http://www.wigwamen.com/housing/locations/ and has most of its properties in the east end). Wigwamen has written letter in support of a C-MP station. Further away, but still within the pedestrian catchment zone is Tobias House at Danforth, and there are more seniors buildings just west of Monarch Park. We’re talking about lots of low-income people who tend to be transit “captives.”

- A Coxwell-Monarch Park station is sited well for transit connectivity: Especially if SmartTrack offers service at TTC fares with TTC transferability, this would be a solid location from Day 1 with good long-term growth potential. At present, the two bus routes that serve Coxwell Avenue handle 55% more riders than the entire Oakville Transit system*. There’s a case for combining the two routes to provide one-seat service all the way from the Beach area, via this proposed ST station and Coxwell subway station, through the hospital/civic centre employment node and all the way up to Eglinton. The case gets stronger as of 2021 when this combined route can eventually link the Eglinton-Crosstown with the Line 2 subway at Coxwell and SmartTrack, likely the only spot in the east end where one bus route could join all three of those key rapid-transit lines. *Using 2015 data, Oakville Transit carried 2.83 million riders a year. The two TTC routes serving Coxwell (Nos. 22 and 70), handle 14,300 riders on an average weekday, which the TTC multiplies by 306 to get an annual figure, in this case, 4.38 million.

- Coxwell-Monarch Park was chosen by experts for the Super GO electrification plan – and that report was produced by transportation professionals – its station-location choices were based on study, not political priorities.

In summary

We have a new provincial government and new ministers of Environment and Transportation, both of whom are people who should see the need to restore the public’s faith in transportation-planning processes. Ontario’s competitiveness and sustainability hinge to a significant degree on regaining a trust damaged by politicians at all levels who interfered with the public service’s ability to fearlessly prepare menus of options, objectively pull together and analyze evidence, and use their professional expertise to speak truth to power. The case of Coxwell-Monarch Park appears to be strong and appears to have fallen through the cracks because of flaws and corruptions in the process. While it would be inappropriate to ask for politicians to demand that this station be added to the SmartTrack project – despite the strong evidence – it’s a crucial matter of provincial interest (municipal and federal, too) that thorough study be done that a) examines the merits of this specific potential station and b) looks seriously at how it could possibly have been overlooked so we can learn from our mistakes and get better results from the processes in the future. And while the lack of a station at Coxwell-Monarch Park might not have a negative impact on a “constitutionally protected Aboriginal or treaty right,” as the criteria at this stage of the process word things, it’s clear that the process has failed people who need better transit and live in the immediate pedestrian catchment zone of this proposed station, including Aboriginal people of Toronto.

Five quick supplementary points we should make in closing

- While SmartTrack has cost and time-frame advantages to offer in a city and metro area that is way behind in building transit infrastructure, it in no way obviates the need to get on with a major new rapid-transit line through Toronto’s core that does not add to the crowding at the Canada’s two busiest transit stations, Bloor-Yonge (415,000 daily platform movements) and Union (275,000). This new major line would most likely be the so-called Relief Line that has been talked about for more than a century and which has been the top priority of knowledgeable transit people on and off for 50 years. At best, we should be looking at SmartTrack as a plan for borrowing capacity that can temporarily be made available on Metrolinx’s surface corridors and at Union to address urgent needs, understanding that Metrolinx must deal with huge regional growth and will almost certainly need it back.

- We should be thinking long-term with regard to the corridor upgrades, looking to what its maximum capacity can be and planning to ensure we can scale up to achieve it at the best price. Metrolinx has been taking an incremental approach, adding a third track on LSE to Scarborough last decade and preparing to add a fourth now. While my sources are not unanimous on this, it would seem they think we should be looking at how we’re going to get to five tracks from Union to Scarborough if we end up with a not-unlikely runaway success akin to London Overground. One respected Metrolinx source says we can do all the local and express service we need with four tracks, while others (Metrolinx and outside), say a fifth track is almost certainly going to be needed sooner or later because the corridor has to serve Via, provide redundancy and anticipate demand growth, and that preparing for it now is better for taxpayers and the residents who have to endure construction in their neighbourhoods. It’s worth noting that the 1974 SuperGO electrification report was calling for five tracks Union to Scarborough.

- It’s time to get serious about making the vast swaths of asphalt surrounding outer GO stations into destinations for much more than parking. If we don’t give people many good reasons to be on outbound trains in the a.m., RER’s new operating costs are going to swamp its revenues. Some elements of MTRC’s rail-plus-property business model is likely the route to take, allowing a Crown corporation to professionally manage a massive real estate portfolio and earn returns for Metrolinx on the public’s investments. Done right, we can defray transit capital costs while expediting operating efficiencies. These lands also need to be the top/only choices for new developments with a public interest such as universities, colleges, hospitals, casinos, etc.

- In the period leading up to the rollout of RER, it’s worth doing a pilot project whereby all transit trips that begin and end within any one GTA municipality have fares capped at that municipality’s single fare. Because it would allow GO and the various local transit agencies to start fully supporting each other, the potential ridership increases might offset the revenue losses to a greater degree than might be expected. We can gain valuable real-world information about the transportation market and how transit can work more efficiently. It should help us to do fare integration intelligently. It should also offer significant rewards at a low risk because, as a pilot, it would have a termination date, if necessary.

- Though I’ve focused on Coxwell, the City of Toronto would be wise to look at how the Birchmount area can be developed. It’s numbers are decent, and it’s an area not at all well-served by transit at present. There are also huge underutilized sites. An ST station there (or near Warden and Danforth as proposed in the 1974 SuperGO report) could be a useful catalyst.

Notes on the contexts for some of the proposed new ST and RER stations

Lawrence-Kennedy is in PD 13, the eighth-biggest market for trips to PD1 (downtown). Transit already has a 75% market share of the trips to PD1, with 11% of the trips being made on GO. The station’s importance rests to a significant degree on the fact the Scarborough Subway Extension plan does not include a station at Lawrence, connecting with Lawrence bus. Prospects for creating new transit riders for trips to PD1 appear limited, though the station has been approved for ST even if the broken out business case has been questioned and was rated “low performing”.

Finch-Kennedy is in PD 16, the ninth-biggest market for trips to PD1. Transit already has a 79% market share, with 16% of trips made on GO. Prospects for creating new transit riders for trips to PD1 are limited in the short term, though Milliken Square Mall and a Public Storage facility present lots of longer-term development land. The station has been approved even if the broken-out business case has been questioned (costs outweigh benefits).

Coxwell-Monarch Park is in PD6, Toronto’s second-biggest market for trips to PD1 (downtown), though transit has only a 52% market share – the lowest of all Toronto planning districts. Less than 0.5% the trips to PD1 are made using GO’s corridor, which runs PD6’s full length. PD6 generates 19% more PD1 trips than PDs 13 and 16 combined, while transit in PD6 has a 31% lower market share of PD1 trips. Not building a station leaves a 4-km gap in an area where SmartTrack may have its best potential to relieve Line 1 and Line 2 crowding. With a 700-metre extension of the TTC’s No. 70 bus, C-MP would connect directly with two routes that carry 55% more daily riders than the entire Oakville Transit system and would link C-MP with an employment hub (5,000+ jobs) at Michael Garron Hospital/East York Civic Centre. This C-MP station would also be 300 metres from a stop on the 506 Carlton streetcar, which carries 40k riders daily. C-MP should score well on Social Inclusivity and Accessibility, having a large TCHC development immediately to the northeast and assisted housing to the immediate south. The site has several development sites within its 800-metre radius area, including Danforth Garage, a.k.a. Coxwell Barns (five acres at Danforth currently undergoing a master-planning process under the aegis of CreateTO), a new building approved at Upper Gerrard and Coxwell, a 0.6-acre site next to station being used for U-Haul vehicle storage and a 0.5-acre building materials site where station entrance would be. How C-MP missed the list of 50 stations that qualified for IBC screening, let alone the short list, is a mystery (even to some Metrolinx staffers who cannot speak on the record). With high current density, travel patterns and low transit-market-share penetration, prospects for creating new transit ridership for trips to PD1 and helping relief effort appear to be very strong at C-MP station.

Birchmount is on the PD13-PD14 boundary. PD13 is the seventh largest generator of trips to PD1 and transit captures 75% of them, in part because it contains Kennedy station, probably the GTA’s second best transit-served hub. PD14 is the 11th biggest generator of trips to downtown, so the market is smaller than average. But there is considerable room for growth as transit captures only 55% of the market share for PD1 trips (third lowest of all PDs), and 30% of the transit trips to PD1 are by GO. Current density in the 800-metre radius is fairly low (but greater than nine of Metrolinx’s 51 mobility hubs). There’s lots of nearby developable and underutilized land, though much of it is exclusively “employment” meaning it would be a challenge to create the mixed-use urbanism in the short term. Birchmount is also within 800 metres of a Neighbourhood Improvement Area, one of the criteria Toronto wanted considered for ST consideration. Prospects for creating new transit ridership are moderate short term, but the potential could be big with zoning changes that allow for development of the Birchmount strip between Danforth Avenue and Danforth Road. Not having a station here leaves 5-km station gap, far too long for connectivity in an area that has transit needs. PD14, in particular, is starved for transit to PD1

St. Clair-Old Weston is in PD3, the fifth-biggest market for trips to PD1. Transit has a 62% market share, but less than 0.5% of trips made on GO. Site borders on huge amounts of former stockyards lands that have been converted to car-dependent big-box retail. Despite current low density, prospects for creating new transit riders for trips to PD1 appear good short term due to apparently unsatisfied demand in PD3. The developable Stockyards land (RioCan property) would require major rezoning and total urbanizing, something that could be done, though our record on such initiatives in Toronto is poor.

Park Lawn is in PD7, the 11th-biggest of 15 markets for trips to PD1. Transit has a 59% market share, and 35% of the trips are made on GO. People-plus-jobs density is not high, at least using the 2011 data that’s referred to in Metrolinx’s reports. But residential density will likely continue to grow considerably for a few years. There are concerns a new station would cannibalize ridership at Mimico and that a replacement of Mimico (especially after recent investments in Mimico station) would be a waste. The closeness of the stations should not be a major concern in that 1-km station spacing (along with flat and transferable TTC fares) may eventually prove to be essential to getting SmartTrack to its full potential. Prospects for creating new ridership for trips to PD1 look moderate, but they’re probably very good long term. The proximity of Mimico station and the lack of office-employment prospects on the old Christie bakery site would seem to indicate there there’s no rush to build this station. Trying to track down 2016 census data because things are changing fast.

Mulock In 2011, the population and employment density within 800 m of the potential Mulock station was estimated to be 32.6 people and jobs per hectare (P+J/ha). The job figures would have included the Magna facility, which is now closed, eliminating 850 jobs. There are two active development applications located within proximity of the potential Mulock station, both of which are minor in nature and do not represent a significant increase in density or change in land use: A new Shoppers Drug Mart store proposed for the northeast corner of Yonge Street and Savage Road; and 28 townhouses proposed on Silken Laumann Road.

Breslau This station was deemed to be high performing in Metrolinx’s rankings, but this report raises questions about how it could possibly have achieved such a label.

http://www.metrolinx.com/en/regionalplanning/newstations/IBC_Breslau_EN.pdf

The report says on page 14: “In 2011, the population and employment density within 800m of the potential Breslau station is estimated to be 0.1 people and jobs per hectare (P+J/ha). The lands surrounding the potential station are currently rural/agricultural and contain only a few houses, a church and a few businesses. Figure 4-1 illustrates the current land use permissions for the proposed station site and surrounding area. In 2006, an estimated 72 residents and 43 jobs were located within 800 metres of the potential Breslau Station. Projections from the Ministry of Transportation Greater Golden Horseshoe Model suggest that by 2031 the population and employment within the Station area may reach 334 and 209 respectively. [1] However, recent changes to policy and planning objectives have resulted in substantially higher population and employment forecasts for the Breslau area. Figure 4-2 shows where recent development has occurred and where development is anticipated within the Secondary Plan Area. The Draft Plan of Subdivision submitted to the Township by Thomasfield Homes shows that in addition to a new GO station, the following will be accommodated on its 94.9 net developable ha of land: 2,535 people; and 2,830 jobs (i.e. 24.6 acres Employment Land (2,450 jobs), 3.7 acres Commercial (116 jobs), 4.9 acres Mixed-Use Commercial (153 jobs) and 3 acres Institutional (40 jobs).” … “Given that the potential Breslau station is located within an undeveloped area, there are no ‘soft sites’ within 800 m of the potential station. Soft sites are considered to be parcels with a relatively high potential for change, such as parking lots and under-utilized sites given current zoning and the Official Plan designations. A new residential subdivision is being completed approximately one km east of the potential station site and considerable new development is underway or planned elsewhere within the Township and the larger Region of Waterloo.

https://observerxtra.com/2016/11/24/omb-upholds-woolwichs-staging-plan-breslau-subdivision/ Breslau plans would bring 6,710 people + jobs to the catchment, roughly 31 per hectare. Strangely promotional language in a Metrolinx document about Waterloo’s connections with Toronto. http://www.metrolinx.com/en/greaterregion/regions/waterloo-wellington.aspx

Innisfil This station is also deemed to be high performing, apparently based on some longer-term projects. From Page 13 of this report

http://www.metrolinx.com/en/regionalplanning/newstations/IBC_Innisfil_EN.pdf

“The existing population and employment density within 800 metres (m) of the potential Innisfil station is estimated to be 5 people and jobs per hectare (P+J/ha). While currently the area does not meet Metrolinx Mobility Hub. Guidelines for rapid transit, significant population and employment growth is anticipated for the South Alcona area. The draft Secondary Plan, which is under appeal, shows a Phase 1 population of 7,200 people and 1,100 jobs. Growth projections for Phase 2 will be subject to each five-year review of the Town’s Official Plan in the future. Figure 4-1 illustrates the land designations from the draft South Alcona Secondary Plan. Surrounding lands are largely designated ‘Agricultural Area’ and will not contribute to the local area density. When fully built, the South Alcona area is intended to have an overall gross density of 67 P+J/ha. Some of the proposed medium density and commercial areas are slightly outside the 800 m station radius. Assuming full buildout future densities within 800 m of the Innisfil station would be 40 to 60 P+J/ha.