Heavy-handed bias in the project’s Initial Business Case undermines the credibility of the report and the project’s proponents, in government and at Metrolinx. The risks of under-building are huge and almost certainly outweigh any possible cost savings being sought. The risks of overbuilding are non-existent.

The following piece ran in the Daily Commercial News in two parts, on Oct. 3 and Oct. 4, 2019. Since then, further capacity concerns have been raised, that the loading standards used for comparing TTC subways with trains for the proposed project skew much closer to crush loads when considering the Ontario Line technology.

By Stephen Wickens and Edward J. Levy

Maybe it’s a coping mechanism, a desperate search for positives from new transit proposals in hopes of staving off a despond that deepens with the sense that, all these years later, we’re still letting politicians micromanage and meddle in the planning process.

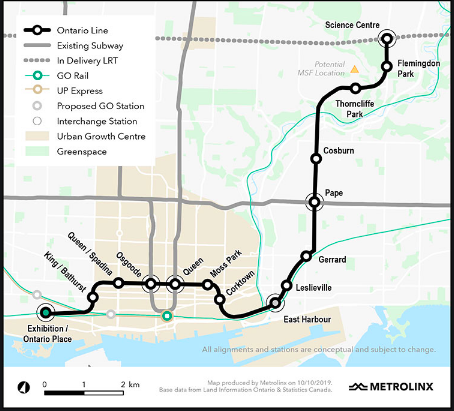

There are merits in the Ontario Line, the latest branding of a proposed subway through Toronto’s core. But after careful review of the initial business case (IBC) and discussions with transit professionals, we can only conclude there aren’t yet enough. The public is being urged to go all in on a high-stakes gamble for a long-overdue piece of infrastructure that stands head, shoulders and torso above the rest in terms of Toronto and GTA needs. Ramifications of even minor demand-forecast errors would be huge and lasting.

It’s good that:

- We’re seeking cheaper ways to build: Default use of deep-bore tunnels — especially when wasted on low-density areas — may be the main reason we’ve spent far too much for far too little new subway in recent decades.

- Ontario Line proponents are pursuing fully automated operation (FAO): Not only can FAO cut labour costs, but standardized acceleration and braking with set speeds on curves and grades can reduce wear on vehicles and tracks, speed service and allow trains to use full platform lengths. But FAO can work with bigger trains and the claim that competitive tendering is possible only with standard-gauge vehicles is bogus.

- Proponents want cross-platform access, simpler physical links between GO and the TTC at key stops (though real benefits won’t materialize until all GO trips that start and end in Toronto are transferable at TTC fares).

- Current momentum may have us closer than we’ve been in 50 years to funding the line best able to add network capacity. It was obvious in 1968 (when Line 2 first reached into Scarborough and Etobicoke) that core parts of the subway were already capacity constrained in rush hours. Yet, in intervening decades, we made lines longer, aggravating core crowding and squeezing many would-be riders off transit altogether.

Alas, the IBC is fundamentally flawed, most notably in that it spends most of its 86 pages on a skewed comparison, repeatedly hammering a no-brainer case that benefits of Queen’s Park’s 15.5-km, 15-station idea might be twice as great as those of the city’s 7.5-km, eight-stop Phase 1 plan. They’d better be.

Even the per-kilometre comparisons are unfair, with only the costliest parts of the city’s long-term Relief Line plan considered. Such heavy-handed bias undermines the report’s credibility.

A proper IBC would provide much more than the Ontario Line proposal versus two thin alternatives — a segment of the city’s long-term Relief Line plan and a business-as-usual option (no new subway at all through the core).

The lack of alternatives is dismissed with an odd 59-word paragraph, claiming “a variety of variations for the Ontario Line alignment were developed.” No hints are offered about what the variations may have been and why they were dismissed. Report authors appear to be saying, “Trust us,” a message that should trigger alarms after decades of politically driven errors.

Let’s hope Metrolinx studied options from when Toronto was good at building subways on time, on budget at prices far below current costs (even after accounting for inflation).

In 1968, for example, a TTC report, two years in the making, considered four options for a Queen Street subway. Those options relied on cut-and-cover tunnels, a generally cheaper and faster method heavily used for 20th-century parts of the system. (Elevated lines tend to be even less expensive but are best suited to broad corridors in low-density areas).

Cost cutting will be key to resuscitating the public will to pay for transit building, but the IBC states — without offering evidence — that Ontario Line estimates “are in line” with the Eglinton Crosstown and the Line 1 extension to Vaughan.

Some light digging indicates the preliminary Ontario Line per-kilometre estimate is actually more than twice that of the Crosstown and nearly twice as much as the York-Vaughan project, the latter being by far our most-costly subway to date, even after adjusting for inflation.

Professionals specializing in technical matters question whether gradients needed to climb from deep tunnels to proposed above-grade stretches are too steep. Some with global experience question whether we can achieve 90-second frequencies in peak periods, especially with four big bends in a “strangely indirect route” through downtown.

It’s been suggested that if serving the much-hyped East Harbour site is a priority, a shorter, straighter alignment through the core (likely under Front and Wellington) makes more sense than Queen Street, even if it means tossing the city’s Relief Line work.

One part of the IBC model assumes there will be “reasonable improvements” to surface transit (which would be a radical departure from trends since the early 1990s). Then we’re told Ontario Line benefits will include reduced costs from streetcar and bus operations (experience shows well-planned new subway capacity increases demand on surface feeder routes).

The report makes no mention of Mayor John Tory’s SmartTrack, which would seem to factor significantly among network assumptions. If Metrolinx is implying SmartTrack will be killed, someone should say so bluntly.

Most importantly, there’s a strong likelihood the IBC lowballs demand, meaning premature crowding is a huge risk. We’re told, without supporting data, the Ontario Line was “designed to deliver capacity to match projected future ridership for 50-plus years beyond opening day.”

We’re not willing to bet that trains 28 per cent shorter and 6.25 per cent slimmer than the ones we overload now will be enough — even short term — for a system so jammed it has driven would-be passengers to other modes for decades.

Seeking savings with more efficient and reduced tunnelling is great, but it must be weighed against risks of underbuilding. The public needs full cost-estimate comparisons pitting the Ontario Line (and other options) against a proposal that includes Phases 1 and 2 of the city’s Relief Line plan and some accounting for full subway on the University Avenue to Exhibition station stretch.

The apples-to-pineapples comparison denies us knowledge of the potential savings — the reward. That leaves us unable to gauge the worth of tradeoff — the risk.

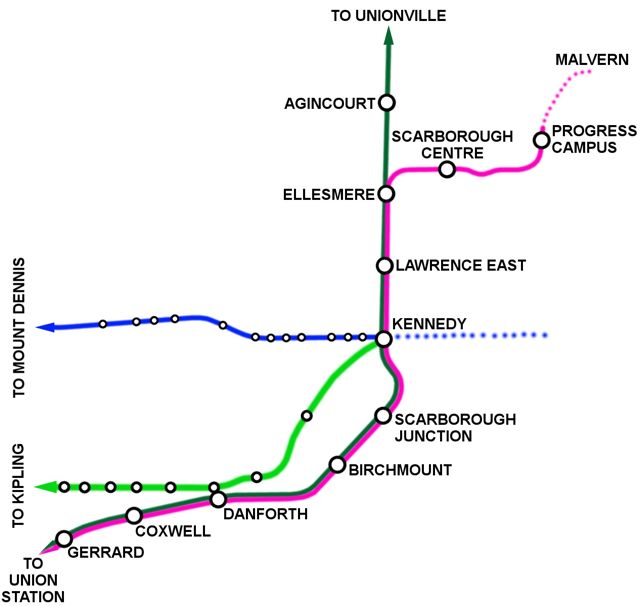

A crucial point usually overlooked in the broader discussion is that the entire east-end TTC network feeds into the long-overloaded Yonge subway.

In the west, the Spadina subway has relieved the Yonge line for 40-plus years and, once GO’s electrification is done, the Barrie and Kitchener lines offer other relief options. At Eglinton, for example, that’s three alternative lines from the west to downtown within 7.5 km of Yonge. East of Yonge there’s no alternative for 11.5 km, and much of that capacity, focused on Kennedy station, loads Line 2, which dumps it back onto platforms and trains Yonge at Bloor.

A hopeful view is that the report concedes design refinements are needed; a pessimistic one is that needed refinements appear massive. We fear the report may be yet another case of politically driven decision-based evidence making, and that viable options have been eliminated without real study.

We get the argument we must start building; we’ve needed a Relief/Ontario Line longer than most Torontonians have been alive. We applaud that the current government seems eager to make it by some variation the “crown jewel” of its transit plan.

But we won’t get a second chance to get relief infrastructure right in our lifetimes. To seriously improve our odds this time, we need a much more robust and credible business case than the one presented in late July.

Stephen Wickens is a Toronto-based journalist and transportation researcher. Edward J. Levy, P.Eng, is a consultant, retired transportation planner and the author of Rapid Transit in Toronto (A Century of Plans, Projects, Politics and Paralysis).