Few will mourn the unreliable orphan foisted on us by provincial bureaucrats who claimed ICTS technology would be a low-cost alternative to subways. But it turns out the troubled RT didn’t just cost more than light rail, it almost certainly cost us more than a subway would have in the first place.

By STEPHEN WICKENS

If there’s a heaven, and if Gus Harris gained entry, you can bet he’s put the harp lessons on hold to follow the Scarborough transit fiasco.

Harris, Scarborough’s mayor for much of the 1980s, opposed the once-futuristic Intermediate Capacity Transit System (ICTS), designed to be a low-cost alternative to traditional subways, which were proving too expensive for suburban applications (at least in the absence of real world-class land-value-capture systems).

In 1981, when Scarborough council snubbed Harris to back a switch from conventional light rail to the province’s unproven technology, he dubbed it “The Toonerville Trolley.” When Metro council finalized the switch weeks later, he said, “I don’t think Scarborough should be guinea pigs for this.”

Minister of transportation James Snow and Kirk Foley, head of the province’s Urban Transit Development Corp., had led Queen’s Park’s hard sell that spring. Future mayor Joyce Trimmer led the majority Scarborough council faction. They were feted by UTDC and flown to Kingston to see it on a test track. They quickly bought in on a promise that ICTS would be a huge step up from the then-new streetcars that had been expected to ply the Kennedy-Scarborough Centre corridor as per a 1977 plan approved by Metro Council.

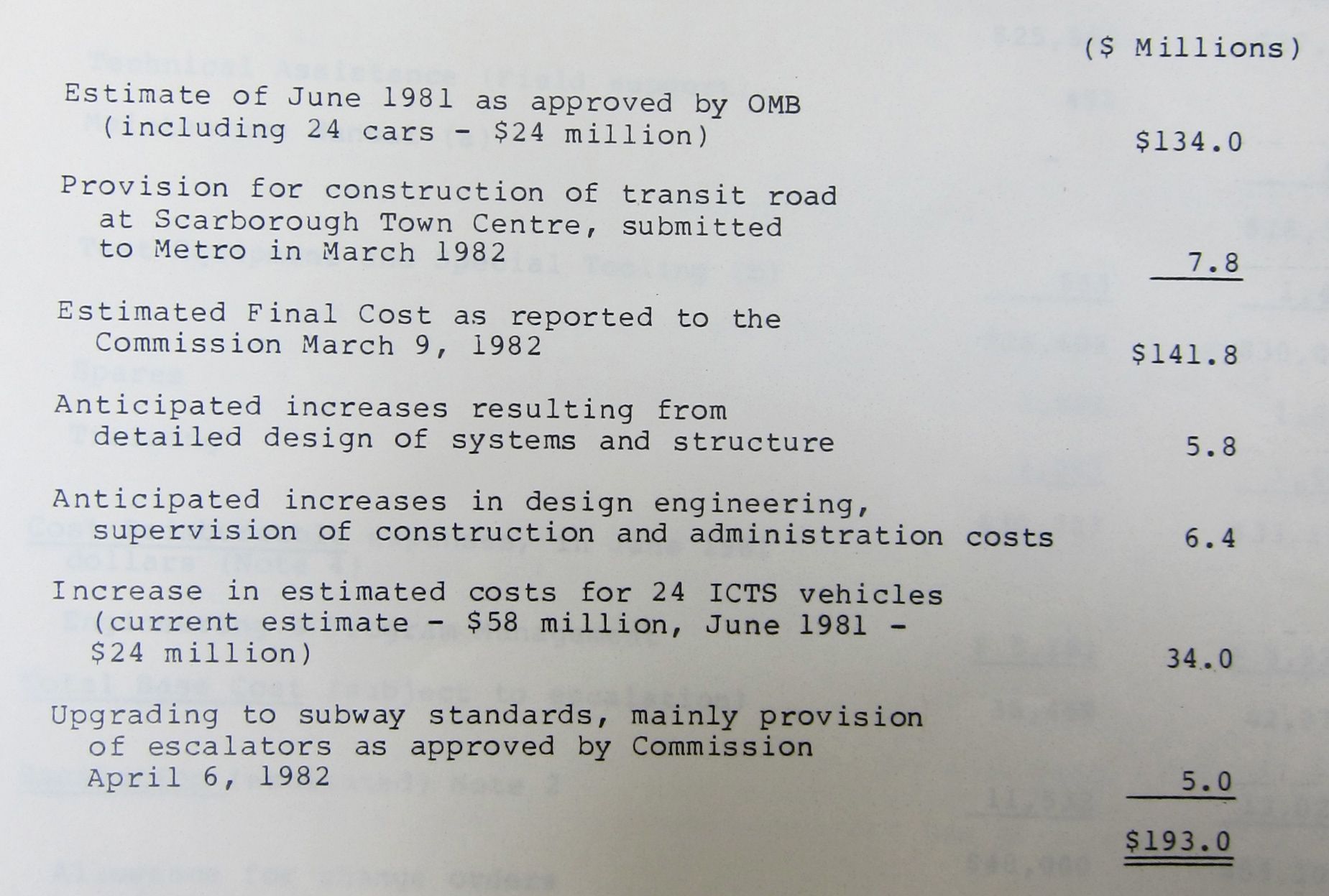

ICTS was to cost $134-million, 24 per cent more than the streetcar option, whose estimate had risen to $108-million by 1981. But Cabinet at Queen’s Park, eager for a working line to showcase UTDC’s driverless ICTS trains to the world, vowed to pick up all extra costs.

So what could possibly go wrong?

A year later, the TTC – a diplomatically reluctant partner in the ICTS plan – announced costs had soared to $181-million. Minutes of an internal meeting available at the archives show the bad news was known months earlier and that the eventual announcement played down the escalation estimates, which had actually reached $193-million.

To the odd person, me, who remembered the subway extensions from Islington to Kipling and Warden to Kennedy had opened in 1980, under budget at a combined cost of $127-million, even the low-balled $181-million RT tab raised red flags.

Might a subway cost less?

It was a simpler time. I simply phoned the main TTC number and was put straight through to a man named Stan Lawrence, who was heading up the RT project. He was friendly when asked if a subway option had been considered. Of course it had, he said, adding that costs and potential alignments had been studied and that the determination was that the best subway would cost slightly more than twice as much as the streetcar option (estimated at $68-million in 1977, likely the last year a subway estimate would have been calculated). When I asked for a specific subway cost and to see the studies, he shut the conversation down, saying the report wouldn’t be made public because only light-rail and the ICTS plan were on the table.

I then called Mayor Harris’s office, and he got back to me about a week later. I told him if Scarborough’s downtown dream was to ever become reality, it probably needed a single-seat connection to Toronto’s core some day. It seemed this was a natural one-technology subway corridor extension of the Bloor-Danforth that shouldn’t be broken up for ICTS or streetcars. (I’ve always liked what light rail can do and I had no problem with a UTDC demonstration line, as long as it went into a fresh corridor elsewhere.)

Harris made clear it was too late to for changes. The Scarborough city council and Metro had made their decisions; the province had taken charge of the file and was footing the bill. There would be no turning back, though Harris, who had backed light-rail all along, suddenly sounded keen to know what a subway would have cost.

Weeks later, Harris called and suggested we go for coffee. He didn’t have much more to say than that he’d been talking with TTC engineering staff who told him a subway extension from Kennedy to Scarborough Centre had indeed been studied and that the cost estimate was between $150-million and $175-million. He also said that some day, “maybe in five, 10 or 20 years, we’ll get to say I told you so.”

SRT problems made frequent headlines in the early years of operation and costs eventually topped $220-million as major modifications were needed. Internally, TTC staff had joked that ICTS stood for, It Can’t Traverse Snow. Harris called it “Lada transit at limo prices,” when I ran into him on Queen Street one day.

In 1989, Harris, no longer Scarborough’s mayor, phoned me with a scoop that there was a serious behind-the-scenes push at the TTC and Metro to scrap the SRT just five years after it opened. Queen’s Park had heard about it and was leaning on politicians and staff to shut up because UTDC had pending sales in Asia. (Neither Asian deal panned out, and the Star’s Peter Howell got the scoop because I was working at a national business paper uninterested in Toronto transit stories.)

It’s total coincidence but highly appropriate that I was reading Barbara Tuchman’s March of Folly on my first SRT ride in the spring of 1985. The sound of the surprisingly noisy vehicles also left an impression.

A few weeks after that initial SRT ride, the TTC and the city released an ambitious rapid transit expansion plan called Network 2011, calling for a Downtown Relief Line and subways on Eglinton and Sheppard. Shortly thereafter, I got to discuss Network 2011 with a senior TTC man, who told me very interesting stuff after he got me to promise that our talk was all off the record. This was, at most, three months after the SRT opened, and he said firmly the TTC would never consider ICTS again. Also of note was that the DRL was the TTC’s clear priority, even if the official story, for political reasons, was that Sheppard should come first.

As for Gus Harris’s $150-million to $175-million estimate for a subway from Kennedy to Scarborough Centre, he said those numbers were accurate, confirming that the province’s low-cost alternative almost certainly cost more than a subway would have in the first place – a particularly galling thought now that it’s near the end of its life just three decades later.

When I suggested the cost-comparison might be the reason for the TTC’s reluctance to release its work on the subway option, he said, again with a warning this was off the record, that the SRT cost was Queen’s Park’s embarrassment. The TTC was probably more worried about public reaction to the fact that extending the subway cost-effectively would require mothballing Kennedy station, which was then just five years old.

Anyway, during the summer of 2013, as the Scarborough debate took bizarre twists, friendly staff at the TTC and City Archives tried, without success, to help me track down that never-released document, probably more than 35 years old, assessing the subway option. Maybe the fact it was never released made it okay to file it by way of a shredder.

I’m dying to see it, in part because there’s a far better alignment than any of the subway options that have been under consideration. There’s a significant chance the TTC had found that better way decades ago.

So, we’re still digging, and the Toonerville Trolley rolls on … for now.